Summary of movement

From April 2016–February 2017 Standing Rock Sioux reservation in North Dakota held the largest gathering of indigenous nations in modern United States history. Tribal members and environmental activists gathered there in opposition to the route of a pipeline, called the Dakota Access pipeline, carrying oil from the Bakken oil fields in North Dakota under the Missouri River half a mile north of Sioux lands. It became the largest Native American protest movement in living memory.

It is a recent example of indigenous resistance to ecological destruction, resource extraction, and political domination by the American state. More than an environmental stance, opposition to this pipeline is part of a decolonisation movement that aims to save Native American land from expropriation, their culture from appropriation, and their resources from exploitation. It is part of a larger civil rights movement for Native Americans.

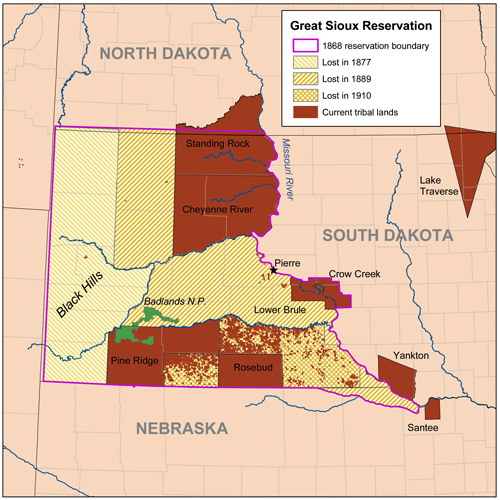

The Sioux is a tribe spread throughout North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Montana, and Minnesota, as well as Canada. The Sioux are further subdivided in seven groups, known as seven council fires, or oceti sakowin, each with a different dialect of a common language. There are four main Lakota Sioux reservations in the US: Standing Rock, Rosebud, Cheyenne River, and Pine Ridge. They have resisted Euro-American rule since the westward expansion of European colonisers in the 1800s.

The current civil rights movement is intertwined with millenarian religion, forming part of a cycle of resistance to American colonial domination through ritual and prayer from the 1890 Ghost Dance to the 1970s American Indian Movement to the protest camps at Standing Rock in 2016–2017. These movements use prayer and dance as forms of religious action anticipating the end of the white colonial social order and the renewal of Native American ways of life. It is a way of reconnecting their community, revitalising their religion, and protesting against injustice.

History/Origins

The recent events at Standing Rock Sioux reservation have been called ‘our Ghost Dance’ by tribal member, lawyer, and activist Chase Iron Eyes (Palma 2016). The Ghost Dance was started in 1889 by Wovoka, who was also known as Jack Wilson, a Paiute living near Walker Lake, in Mason Valley, Nevada. His father had been a shaman and medicine man, recognised by the community as a spiritual leader. From childhood Wovoka claimed to hear voices and see visions.

During the eclipse of 1 January 1889, he had a vision in which he saw all the dead alive again, happy and youthful. He received a message from God to share with others. Through the vision he also claimed to have received the ability to control the weather and later became known as a weather-doctor. Afterwards, Wovoka preached non-violence and right living. Fighting, drinking alcohol, and telling lies were forbidden. Wovoka claimed he was ‘a messiah like Jesus but not the Christ of Christians’ (Kehoe 2006, 6). Wovoka prophesied that the earth would be renewed, the dead would live again, the bison herds would come back, and the whites would disappear. The Native Americans would live without sickness, misery, or death, young and happy forever. Wovoka died in 1932.

The main ceremony of the Ghost Dance was the circle dance, which was a transformation of the traditional Paiute circle dance. It spread quickly throughout the tribes of the Western USA. The main period of activity was 1890 but the dance continued in some areas until mid-20th century. The last known adherent died in the 1980s.

It was called the Ghost Dance because the resurrection of the dead was part of the renewal of the earth. The Paiute word for the practice meant ‘dance in a circle’. The Sioux term meant ‘spirit dance’ and the English translation seemed to derive from that. The core of the religion was a creed that a ‘clean, honest life’ is the only good life (Kehoe 2006, 9). It was a mix of Christianity and Mormonism with traditional Native American religion.

The emphasis was on dance, prayer, and right living. This was all the Ghost Dancers needed to do to effect change. The transformation would happen through supernatural means. It would be experienced as an earthquake. There was no need to fight the whites as they would cease to exist as part of the natural transformation of the earth. The transformation was expected to happen in the spring of 1891.

A Sioux delegation visited Wovoka in 1889. One of the party, Kicking Bear, told of a special shirt that dancers received that would stop bullets, although this was not part of Wovoka’s teaching. It was something he had heard about probably from the Arapaho (Andersson 2008, 69). During the spring of 1890 participation in the Ghost Dance increased massively. It was a time of millenarian expectation among the Lakota Sioux. There were many dances at Standing Rock and the other Sioux reservations.

Conditions were hard following the break-up of Great Sioux Nation in which the United States ceded land from the Sioux that had been guaranteed under the 1851 and 1868 Fort Laramie treaties, including the sacred Black Hills. This meant the Sioux lost their hunting lands. The remaining land was not suitable for European-style mixed farming enforced by the US government. The Sioux were facing famine and starvation.

US government policy was to make the Sioux live as white men, as individual farm owners and homesteaders, practising Christianity. Their children were sent to mission schools, where they were punished for speaking their own language. Given these conditions, the Ghost Dance promised renewal and hope. Dancing was a way for the community to come together, strengthening Native ways.

According to anthropologist Alice Beck Kehoe, ‘for the Teton Sioux (Lakota) in 1890, the messiah in the West was hope out of the chaos into which they had fallen’ (2006, 39). They had seen the bison herds disappear. The bison were the manifestation of the Great Spirit’s gift of life to the Lakota. Their disappearance meant this gift had been withdrawn. The Ghost Dance predicted their return. This was nothing less than the return of the Sioux way of life and means of subsistence.

However, Kehoe argues that the Lakota ‘distorted’ Wovoka’s peaceful religion into ‘a millenarian movement yearning for utopia’ (2006, 40). Andersson sees it as the sort of ‘religious-prophetic’ revitalisation movement common to indigenous peoples globally when they come into contact with Euro-American cultures as a response to the devastation and domination they thus experience (2008, 23).

Dozens of Indian languages repeated the message, ‘There is a new messiah, and he is an Indian. There is a sacred dance you must learn and songs you must sing. Soon the Indian dead will live again and the white men will be swallowed up. The messiah’s name is Wovoka and he is an Indian like us’ (Wright 1998, 3).

However, it was seen as a form of anti-government rebellion by white settlers. Army officers, Indian agents, missionaries, and others around the reservations were agitating for it to be suppressed. They were afraid of the Ghost Dance. The Battle of Little Bighorn (known to the Lakota Sioux as the Battle of Greasy Grass) had occurred in 1876, which was a significant defeat of the 7th Cavalry of the US army under General Custer. One of the famous Lakota Sioux leaders in that battle was Sitting Bull, who resided on Standing Rock reservation and held authority as a chief. There was ongoing tension between the Lakota and the white settlers on the Sioux reservations.

By the winter of 1890, the Lakota Sioux were holding near continuous dances. Schools, farms, and trading posts were abandoned. The Lakota were not living and behaving in the manner of white Euro-Americans as the Government required. This was seen as an act of defiance. The local Indian Agents ordered their rations cut. However, the Lakota Ghost Dancers were not afraid of the authorities. Their ghost shirts would protect them from their enemies’ bullets. This behaviour was also suspicious and worrying to the whites. The Lakota Sioux were falling on the ground shaking with visions during their dances. This was seen as heretical, primitive, and savage by the Euro-American Christians living on the reservations.

As a famous chief, Sitting Bull was blamed for the Ghost Dance although he did not seem to practise or believe in the religion. However, he did allow it to continue among his people after the Standing Rock Bureau of Indian Affairs agent, James McLaughlin, told him to put a stop to it. The Standing Rock reservation was ‘the center of the ghost dance religion’ (Andersson 2008, 65). The situation was volatile and violence between the whites and the Lakota seemed likely. In order to head off the tension, McLaughlin tried to arrest Sitting Bull because he was a ‘troublemaker’ in McLaughlin’s view. When his men tried to take Sitting Bull to jail, some Lakota tried to stop the arrest, and shots were fired. Sitting Bull was killed in the crossfire.

After Sitting Bull was killed, many Lakota fled Standing Rock to the Cheyenne River Sioux reservation. Big Foot was the only Ghost Dance leader left. He led a band of 120 men and 230 women and children from Standing Rock to Pine Ridge reservation to join other Ghost Dancers. The 8th Cavalry Soldiers under Lt Col Edwin V Sumner were sent to watch Big Foot and the Ghost Dancers. The Lakota were afraid that the Army was sent in to kill them. Some of the 500 soldiers included those previously commanded by General Custer at the Battle of Little Bighorn, whom the Lakota suspected wanted revenge (Brown 1970, 441–442).

The 8th Cavalry stopped Big Foot’s group at the village of Wounded Knee. On the morning of 29 December 1890, they rounded up and disarmed the Lakota men. One, Black Coyote, deaf and mute, kept his gun; when a soldier grabbed him, he pulled the trigger. The soldiers opened fire on the whole group. This event became known as the Wounded Knee massacre. Approximately 146 Lakotas died on the battlefield, and an unknown number later. Sources vary on the total number of casualties between 150 and 300. Only 25 soldiers died. The soldiers cut down women and children as they fled. They desecrated corpses and dumped them in a mass grave in a canyon. The massacre led to further skirmishes between the Lakota and the US army. A full-scale war seemed likely. However, the Ghost Dancers surrendered on 13 January 1891. Many subsequently gave up the dance. It had not helped them. They could not fight the US army.

This was not the only massacre of Lakotas by the US Army. In 1863, 300–400 Lakota were killed in the Inyan Ska (also known as Whitestone) massacre, 50 miles from the site of the 2016 protests against the Dakota Access pipeline in the Standing Rock reservation (Allard 2016). These killings are part of Lakota history. They inform the recent opposition to the pipeline. The Lakota see these historical events as connected to their present situation. They are part of a continuous cycle of oppression, colonisation, and murder of the Lakota by white Euro-American society.

In 1968, the American Indian Movement was co-founded by Dennis Banks. This was part of the civil rights movements of 1960s, inspired by the example of Black Panthers. The AIM asserted ‘Red Power’, or equal civil rights for Native Americans. The AIM was active from 1968 to 1973. It began by helping to prevent police brutality against Native Americans. Its remit widened to addressing numerous forms of racial bias and social, economic, and environmental injustice against Native Americans. AIM members occupied Alcatraz, Mount Rushmore, and the Bureau of Indian Affairs building in Washington, D.C. as part of an ongoing campaign to highlight the treatment of Native Americans by the American state. Acts such as the Mount Rushmore occupation also symbolically reclaimed areas that the Lakota Sioux saw as rightfully theirs under the 1868 Fort Laramie treaty.

However, the biggest event in terms of AIM activity was the standoff at Wounded Knee. A group of AIM activists occupied the site of the 1890 massacre. This led to a 71—day siege on the Pine Ridge reservation (Chertoff 2012). They were surrounded by FBI and Bureau of Indian Affairs agents, who continually shot at them, and cut off their supplies and electricity. Federal agents killed two Native Americans during the siege.

The political civil rights movement was also a movement for spiritual revitalisation. AIM leader Dennis Banks, an Ojibwe from Minnesota, first reconnected with his spirituality through Lakota rituals. Like many of his generation, he was raised in white boarding schools, separated from his culture, family, and language. He learned the Sun Dance and sweat lodge rituals. The AIM occupation of Wounded Knee was also called a ‘ghost dance’. Spiritual leader of the AIM, Leonard Crow Dog, said of the siege, ‘we are going to Ghost Dance for the people buried here in that ditch. There won’t be no coffee break’ (Banks 2004, 181).

Even after the westward expansion of white settlers was complete, many Native American tribes still faced disruptions to their land, often in the form of resource extraction and development. In the 1950s a significant section of the Standing Rock reservation was flooded by the Army Corps of Engineers in the construction of a dam on Lake Oahe. This was part of the Pick-Sloan plan for water management of the Missouri River approved by Congress (Capossela 2015). The aim was to help regulate irrigation, control flooding, and provide infrastructure for hydroelectric power. Reservoirs created through this project disproportionately inundated Standing Rock Sioux lands, which were rebated by the government for pennies on the dollar, far less than they were worth, a subsequent Joint Tribal Advisory report found (Howe and Young 2016).

This was part of a history of bad faith and broken treaties between the US and the Lakota Sioux, which resulted in the loss of resources for the Sioux. A significant action in this history was the abrogation of the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty, which maintained the lands of the Great Sioux Nation in perpetuity for ending their war with the US (Mufson 2016). Land could only be ceded with the consent of three-quarters of adult Sioux males. The US government tried unsuccessfully to get the required number of signatures, then seized the gold-rich Black Hills anyway, and reduced the Sioux land to four small reservations. The site of the Dakota Access pipeline goes through land guaranteed to the Lakota Sioux under the 1868 treaty but that has long since been expropriated by private landowners, then sold to Energy Transfer Partners, the company behind the new oil pipeline.

The current opposition against the pipeline is part of this long history of taking Sioux and other Native American land for white use, by homesteaders in the 19th century and by corporations in the 20th and 21st centuries. According to Lakota scholar Vine Deloria Jr, who was born on Standing Rock reservation, the underlying aim of the US government policy to assimilate Native Americans is to take their resources (2003, 2). If their land is held by individuals, not communally as a tribe, it can be parcelled off and sold, and the resources extracted for profit. The resources thus extracted add to the fossil fuel economy that is a driving force behind anthropogenic climate change. Climate change is seen by many activists as a form of environmental racism in which land and resources taken from indigenous peoples are degraded and the aftereffects of pollution are suffered disproportionately by those peoples (Lukacs 2016).

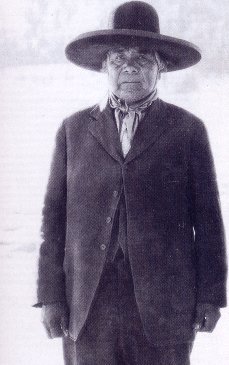

Helen Red Feather, Voices of Standing Rock tribe

Beliefs

Broadly speaking, traditional Native American religion is based on the interconnectedness of all things although there is a wide variety among different tribes as to how this is expressed. Humans are not separated from nature; both are part of the sacred (Deloria 2003). The spiritual world and the physical world are not separate, matter and spirit are not opposed (Morrison 2000). Animals, plants, sun, moon, and objects are viewed as ‘persons’. The relationship of humans to nonhumans is that of kin. (For millennial beliefs, see below.)

For the Lakota, there is no life without religion, ‘religion was an inseparable part of everyday life’ (Andersson 2008, 48). There is a general spiritual force in the visible and invisible worlds, called Wakha Thaka in Lakota, or Great Spirit. Seeing spirits and having visions, as in the Ghost Dance, is considered normal. Spirits give gifts if paid proper respect and attention, but they become dangerous if not. The ultimate aim for Lakota is to be good relatives, to the water and land as well as to other humans (Deloria 1998, 25). Disrupting the river, by building oil pipelines that could leak, would not be the act of a good relation. It would not be paying proper respect, so dangerous outcomes become more likely.

Traditional religion was forbidden on reservations from 1883 until the 1930s. Native Americans were not allowed to practise their ceremonies. Missions converted some to Christianity. The Ghost Dance was a way of reaffirming and revitalising traditional religion in 1890. Now the dances and prayers are again part of reaffirming traditional Native definitions of the sacred.

The emphasis is on peace not war. This was strong in the Ghost Dance and also in the contemporary Standing Rock movement. The Lakota call their obstruction of the pipeline a prayer not a protest. Prayer is a form of protest because spirituality and politics are interconnected rather than separate. The Lakota see a continuity from the Ghost Dance to the American Indian Movement to Standing Rock. As Lakota activist and rapper, Prolific, says, ‘our existence is our resistance’.

The opposition to the pipeline is not solely anti-industry or environmental, it is also a religious issue. The Lakota are protecting their sacred land and space. The river is itself sacred: ‘At the confluence of where those two rivers met was a great whirlpool that created perfectly round stones that were considered to be sacred,’ according to Jon Eagle Sr, the Standing Rock Tribal Historic Preservation Officer (Campbell 2017). The motto of the stand against the pipeline was: ‘Defend the Sacred’.

Tim Mentz Talks about the Destruction of Sacred Sites by the Dakota Access Pipeline

However, the impact reports of the US Army Corps of Engineers for the pipeline revealed a limited understanding of Lakota religion. The Lakotas say that they were not respected or listened to in the process of approving the pipeline. The river was not considered to be ‘real’ religion or a ‘real’ sacred site because it did not fit the European form of religion. There was no evidence of buildings or burials. There was nothing built there that to the Euro-American perspective signified the sacred.

The stand against the pipeline is, for the Lakota, a freedom of religion issue. The earth is inherently sacred and so they believe it is their religious duty to protect it from extractive industries. The Earth is the mother of all creatures. They have a spiritual connection to the land and the water. Another motto for the movement is the Lakota phrase Mni wiconi which means ‘water is life’ or ‘water is alive’. Mni Sose (Lakota for the Missouri River) is a relative. The Lakota want to protect their relative from contamination from the Dakota Access pipeline (Dhillon and Estes 2016).

Water has personhood for the Lakota; it has rights. Those involved in the opposition to the pipeline called themselves water protectors not protesters. Stone circles in the Missouri river in Standing Rock reservation are used for rituals that connect the past to the present and allow completion of the individual and the tribe. These sacred sites must be left undisturbed, in the Lakota view; no minimisation of harm is possible. The destruction of sites is interpreted as a destruction of their religion.

Native peoples in the Americas understand the universe as alive and sentient. All phenomena are understood to be a distinct expression of life force, or spirit. Since all persons—the human and the other-than-human, such as plants, animals, rivers, winds, and mountains—are expressions of spirit, they are recognized as interconnected and contingent. They are relatives. The people seek to honour life force through prayer and ceremony because it has given them life and continues to secure their survival. This field of connectedness, often referred to as the spirit world, responds dialectically to minute (and concentrated) propitiations by the people in order to effect change on their behalf. (Avalos et al 2016).

Millennial Beliefs

The focus on renewal and revitalisation through peace and prayer came from the Ghost Dance of 1890. The Ghost Dance was strongly millenarian. Wovoka was seen as a messiah who foretold that the dead would return, the whites would disappear in an earthquake, and there would be no hunger or disease. The Native Americans would live in a paradise on earth. A potent symbol of the earth renewed was the return of the bison. Ghost dancers reported having visions of their dead relatives returned driving herds of bison.

The Ghost Dance ‘was nativistic, eschatological, religious-political, and messianic; its object was to create a new kind of world; and it was born at a time when the military resistance of North American Indians had been crushed—a time when most Indian cultures were in deep crisis and the Indians were forced to live on reservations set aside for them by the U.S. government’ (Andersson 2008, 24).

Through the Ghost Dance, Lakota Sioux were able to come together as a community and practise their religion at a time when their communities were broken and their religion outlawed. Dancing was an effective form of prayer for them. They danced to change the world. It was a return to the old ways. It was a way to make the whites disappear without fighting. In the face of an unbeatable enemy and the destruction of their way of life, prayer and dance brought hope for spiritual and material renewal.

Christian-influenced messianic millenarianism is combined with the Lakota view of time as cyclical. The circle is another sacred symbol in traditional Lakota religion (Andersson 2008, 52). Many things in nature operate in circles such as seasons and planets. Dances were held in circles and camps built in circles to evoke this in ritual. In terms of time, the cyclicality suggests that what has happened before will happen again. Dennis Banks of the American Indian Movement talks of circle dances bringing Native Americans together again in a ‘Sacred Hoop’ so that ‘we were becoming what we once had been’ (2004, 186).

Standing up against white domination links with renewal of Native American religion and politics in the 1890 Ghost Dance and the American Indian Movement in the 1960s and 1970s and the protests at Standing Rock in 2016–2017. The Lakota were becoming again what they had once been. Each time resistance is called a ghost dance. Prayer is used to influence wider events. Chase Iron Eyes called the recent opposition to the Dakota Access pipeline ‘our Ghost Dance’ that gives the Lakota hope amid tragedy and a feeling of having a hand in their own destiny (Palma 2016).

The Lakota Sioux call the Dakota Access pipeline the ‘black snake’. The black snake is a symbol in an apocalyptic prophecy. Lakota Sioux tribal lawyers cited in court documents filed in 2017 against the pipeline that ‘the Lakota people believe that the pipeline correlates with a terrible Black Snake prophesied to come into the Lakota homeland and cause destruction’ (Harris 2017). The black snake is a harbinger of the end of the world.

However, James Giago Davies, an Oglala Lakota correspondent at the Native Sun News Today, claims this prophecy was invented as part of the protests against oil pipelines. He states that there is no evidence of it prior to the 2014 Keystone XL pipeline protest in Washington, D.C. (Davies 2017).

Other Lakota prophecies offer hope. Tim Mentz, a Lakota Sioux historian, says that ‘the prophecy be fulfilled that our seventh generation will walk back to these sites to save the Nation and our spiritual way of life’ (Palma 2016). The prophecy of the seventh generation, attributed by some to the 19th century Oglala Lakota war leader Crazy Horse, concerns ‘a time when the young take a stand for the future’ (Dhillon 2016). It predicts a time of social, political, and religious renaissance for the Sioux and all Native peoples of North America.

Practices

The Standing Rock Sioux camps that blockaded the route of the Dakota Access pipeline in North Dakota were founded on practices of nonviolence, prayer, and direct action. Protesters stood in the river as a symbol of protecting the water. They formed human chains in front of construction equipment. The Oceti Sakowin camp and later the Sacred Stone camp were established in April 2016 by LaDonna Brave Bull Allard, on her family’s land on Standing Rock Reservation, as centres of peaceful and spiritual resistance to the Dakota Access pipeline and cultural preservation. Oceti Sakowin is the name for the council of Sioux tribes, and also the mythological origin of the Dakota people (Andersson 2008, 320).

Creating the camps was an act of continuous ceremony. Circle dances were held at the camps. Through prayer, singing, and dancing participants aimed to bring the protection of the earth and water into being. Holding camps in this way is part of Sioux tradition. Historically during summer months the Lakotas joined together in camps and held ceremonial dances, including the Sun Dance, and hunted buffalo (Andersson 2008, 7).

The camps were run on donations, brought by other Native American tribes and First Nations, non-profits, online crowd-funding sites, independent individuals, military veterans, and the Black Lives Matter movement. A sacred fire was kept burning in the ceremonial area, with the idea that when it went out it was time to leave. At its height there were thousands of people in the camps (Smith 2017). The camp had seven kitchens to feed everyone present for three meals a day. Eating together is an important part of Native American social life.

The camps were essentially a small town, with basic services, portable toilets emptied each day, doctors, lawyers, herbalists, and a school. There were committees for organisation, including a cultural committee that organised a canoe contest to boost morale. They also practised a limited form of self-rule; for example an attempted rapist was ostracised by the women’s council rather than reported to the police (Elbein 2016). Keeping the camp clean was important in order both to respect the earth and defend the protesters from negative news reports. Since the protest was against an oil company, they tried to use alternative power sources where possible. A large lorry was used as a refrigerator that was run by donated solar panels.

There were varying levels of commitment among those present at the camps. Some were there all the time, organising, volunteering, and assisting in the communal life of the camps. Others were ‘weekend warriors’ coming at the weekends and then returning to their regular jobs and lives in the week. Some came for short periods and left, others just dropped off donations. Hundreds of flags of indigenous nations supporting the camps stood at the perimeter. Some visited to leave a flag, some were long time campers, and some sent a flag by mail as a show of support. There was also a Palestinian flag and a rainbow LGBTQ flag that suggest an allegiance with other social and political justice movements.

In December 2016, tribal chairman Dave Archambault II told everyone to go home, as nothing would happen during the winter. The North Dakota winter was too cold to continue camping safely. Then-President Barack Obama had ordered the Army Corps of Engineers to rescind the Dakota Access permit. This also followed the Lakota Sioux tradition of breaking up into small groups for the winter after a period of ceremony and hunting in the summer (Andersson 2008, 7). The camps returned in January 2017 until they were evicted on 23 February 2017 after the then new President, Donald Trump, granted the Dakota Access pipeline permit (Smith 2017).

After the camps were closed, the Lakota continued their activities to stop the Dakota Access pipeline. There was a march on Washington on 10 March 2017 (Gambino 2017). A delegation from the Standing Rock reservation spoke on the issue at the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues at the United Nations on 25 April 2017. Legal challenges against the pipeline are ongoing (Ellis 2017).

One Year at Standing Rock

Controversies

The use of law enforcement and the army against the resistance of indigenous people has a long history in the United States. The fear among white settlers of a Native American uprising was strong in the 19th century and indirectly led to the massacre of Lakota Sioux by the US army at Wounded Knee in 1891. There was violence on the Pine Ridge reservation during the siege at Wounded Knee in 1973 that led to the killing of two Native Americans by federal agents. The legacy of Wounded Knee and compensation for broken treaties are ongoing legal and moral issues for the Standing Rock Lakota (Gonzalez and Cook-Lynn 1999). The difficulty of remaining peaceful in the face of violent oppression was an issue for the Lakota Sioux in the Ghost Dance and the American Indian Movement as well as at the 2016–2017 protests at Standing Rock.

The protest camps were established in April 2016. An emergency injunction was filed against the Dakota Access pipeline by the Sioux’s tribal lawyers in September 2016. There were an estimated 700 people camping full-time by October, with thousands joining at weekends (Von Oldershausen 2016). Violence erupted between protesters, police, and private security hired by Energy Transfer Partners, the company behind the Dakota Access pipeline, in September – November 2016. Instructed by then-President Obama, the Army Corps of Engineers denied the required easement for drilling underneath the Missouri River in December 2016. The new President, Donald Trump, allowed the pipeline in January 2017. The Army Corps of Engineers ordered the shutdown of the camps in February 2017, ostensibly in advance of the spring flooding season.

Dakota Access Pipeline Company Attacks Native American Protesters with Dogs & Pepper Spray

The pipeline is a desecration of sacred sites according to the Lakota Sioux. The route of the pipeline crosses the Missouri River above the tribe’s drinking water facilities. A previous route that went near the city of Bismarck was rejected on grounds that a spill could threaten the water supply (Dalrymple 2016). To the Lakota Sioux, this change is interpreted as racist, suggesting that it is acceptable to endanger their water supply but not the (predominantly white) city of Bismarck’s. They also raised issues of sovereignty and land use. The land the pipeline goes through is claimed by the Lakota Sioux under the 1851 and 1868 Fort Laramie treaties. They see the pipeline as an example of the US government favouring private corporations over indigenous tribes. The government breaks treaties with the Lakota Sioux but keeps contracts with private corporations. They also find the issue of what can be owned and what the land can be used for controversial. If water is a person, it cannot be owned. What is personhood is a cultural distinction. Under US law, corporations are persons, but rivers are not (Valandra 2016).

Tribal sovereignty is also a controversial issue in this case. The Lakota Sioux are a nation, recognised as such under federal law. However, they argue that Energy Transfer Partners has not maintained a nation-to-nation relationship. The Lakota Sioux were not included in consultation on the project in this manner, but as a local stakeholder. Tribes have since 1992 had the right to be consulted whenever a federal agency approves or conducts a construction project from the outset of the project as government to government collaboration. The Lakota’s legal case rests on the claim that this right was infringed by the Dakota Access pipeline. Also, that the Missouri River is the tribe’s only water source. If the pipeline leaks or spills it would destroy this, and as such the pipeline should be prevented under the Clean Water Act. However, the Lakota Sioux failed to get an injunction stopping construction as of June 2017.

The Energy Transfer Partners’ standpoint is that there are already eight pipelines crossing under the river at the same location. The Dakota Access pipeline will be lower than these so less likely to cause dangerous spills. It does not cross Standing Rock reservation land. It is deep underground. It is the best way to get oil from the Bakken oil fields to the market. It is safer than truck or rail. The Standing Rock Sioux water source is 70 miles from the pipeline. Oil began flowing through the pipeline on 1 June 2017.

Violence occurred between protesters, private security firm TigerSwan, and Morton County sheriff department in September–November 2016 (Montoya 2016). Police used water cannons, rubber bullets, concussion grenades, pepper spray, assault rifles, helicopters, sound cannons, infiltrators, and dogs against protesters. There were 750 arrests between August 2016 and February 2017. There were reports that after arrest protesters were held in dog kennel-style cages. The violence against protesters has been described as ‘state-sanctioned racial violence’ (Pulido 2016, 6). Morton County sheriffs were likened to descendants of General Custer. For their part, the local police described the camp as an ‘ongoing riot’ in a Facebook Post. There were injuries to protesters. Sophia Wilansky lost an arm after being hit by a concussion grenade (Moynihan 2016). The camps were burnt in February 2017 when leaving, which drew criticism but which the Lakota Sioux described as a way of cleansing the camp. There was also criticism of the litter left behind after protesters left.

“Black Snakes” by Prolific the Rapper x A Tribe Called Red

“Stand Up / Stand N Rock #NoDAPL”

Further Information

Academic references

Andersson, R.-H. 2008. The Lakota Ghost Dance of 1890, University of Nebraska Press.

Avalos, N., Grande, S., Mancini, J., Mehta, R., Neely, M. and Newell, C. 2016. “Standing with Standing Rock.” Hot Spots, Cultural Anthropology website, December 22, https://culanth.org/fieldsights/1024-standing-with-standing-rock

Banks, D. & Erdoes, R. 2004. Ojibwa Warrior: Dennis Banks and the Rise of the American Indian Movement, University of Oklahoma Press.

Brown, D. A. 1991. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West, Vintage.

Capossela, P. 2015. “Impacts of the Army Corps of Engineers’ Pick-Sloan Program on the Indian Tribes of the Missouri River Basin”. Journal of Environmental Law and Litigation 30: 143–218.

Deloria, E. C. 1998. Speaking of Indians, University of Nebraska Press.

Deloria, V. 2003. God is Red: A Native View of Religion 3rd ed., Fulcrum Pub.

Dhillon, J. 2016. “'This Fight Has Become My Life and It’s Not Over': An Interview with Zaysha Grinnell.” Hot Spots, Cultural Anthropology website, December 22, https://culanth.org/fieldsights/1017-this-fight-has-become-my-life-and-it-s-not-over-an-interview-with-zaysha-grinnell

Dhillon, J. and Estes, N. 2016. “Introduction: Standing Rock, #NoDAPL, and Mni Wiconi.” Hot Spots, Cultural Anthropology website, December 22, https://culanth.org/fieldsights/1007-introduction-standing-rock-nodapl-and-mni-wiconi

Dhillon, J. and Estes, N. 2016. “Standing Rock, #NoDAPL, and Mni Wiconi.” Hot Spots, Cultural Anthropology website, December 22, https://culanth.org/fieldsights/1010-standing-rock-nodapl-and-mni-wiconi

Howe, C. and Young, T. 2016. “Mnisose.” Hot Spots, Cultural Anthropology website, December 22, https://culanth.org/fieldsights/1016-mnisose

Gonzalez, M. & Cook-Lynn, E. 1999. The Politics of Hallowed Ground: Wounded Knee and the struggle for Indian sovereignty, University of Illinois Press.

Kehoe, A. B. 2006. The Ghost Dance: Ethnohistory & Revitalization 2nd ed., Waveland Press.

Montoya, T. 2016. “Violence on the Ground, Violence Below the Ground.” Hot Spots, Cultural Anthropology website, December 22, https://culanth.org/fieldsights/1018-violence-on-the-ground-violence-below-the-ground

Morrison, K. M. 2000. “The Cosmos as Intersubjective: Native American other-than-human persons”. In G. Harvey, ed. Indigenous Religions: A Companion. Cassell, 23–36.

Pulido, L. 2016. “Geographies of race and ethnicity II”. Progress in Human Geography, 1–10. Available at: http://journals.sagepub.com/do....

Spice, Anne. 2016. “Interrupting Industrial and Academic Extraction on Native Land.” Hot Spots, Cultural Anthropology website, December 22, https://culanth.org/fieldsights/1021-interrupting-industrial-and-academic-extraction-on-native-land

Valandra, Edward. 2016. “We Are Blood Relatives: No to the DAPL.” Hot Spots, Cultural Anthropology website, December 22, https://culanth.org/fieldsights/1023-we-are-blood-relatives-no-to-the-dapl

Wright, J. B. 1998. Montana Ghost Dance: essays on land and life, University of Texas Press.

Documentaries and Other Resources

Awake: A Dream from Standing Rock. Available at: https://awakeadreamfromstandingrock1.vhx.tv/products/pre-order-awake-a-dream-from-standing-rock

Positive review:

Merry, S. 2017. “A new Standing Rock documentary shows how film can give voice to those who feel powerless,” Washington Post. April 13. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/entertainment/a-new-standing-rock-documentary-shows-how-film-can-give-voice-to-those-who-feel-powerless/2017/04/12/e2da02d4-1dfb-11e7-ad74-3a742a6e93a7_story.html?utm_term=.7ecb83a8cf03

Negative review

McAleer, P. 2017. “Film Review: “Awake: A Dream from Standing Rock,” is Full Scaremongering Claims and No Evidence,” Townhall, April 24. Available at: https://townhall.com/columnists/phelimmcaleer/2017/04/24/film-review-awake-a-dream-from-standing-rock-is-full-scaremongering-claims-and-no-evidence-n2317169

Podcasts

Brady, J. 2016. “For Many Dakota Access Pipeline Protestors, the Fight is Personal,” NPR, November 21. Available at: https://www.npr.org/player/embed/502918072/502918073

Gault, M. 2017. “On the front lines at Standing Rock,” Reuters, April 20. Available at: http://uk.reuters.com/article/us-warcollege-19apr-idUKKBN17L2MH

Online Works

Advisory Council on Historic Preservation. 2005. “Consulting with Indian Tribes in the Section 106 Review Process,” August 22. Available at: http://www.achp.gov/regs-tribes.html

Allard, L. B. B. 2016. “Why the Founder of Standing Rock Sioux Camp Can’t Forget the Whitestone Massacre,” Yes Magazine, September 3. Available at: http://www.yesmagazine.org/people-power/why-the-founder-of-standing-rock-sioux-camp-cant-forget-the-whitestone-massacre-20160903

Archambault, D. 2016. “Taking a Stand at Standing Rock,” New York Times, August 24. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/25/opinion/taking-a-stand-at-standing-rock.html?_r=0

Associated Press. 2016. “Guards accused of unleashing dogs, pepper-spraying oil pipeline protesters,” CBS News, September 5. Available at: http://www.cbsnews.com/news/dakota-access-pipeline-protest-turns-violent-in-north-dakota/

Chertoff, E. 2012. “Occupy Wounded Knee: A 71-Day Siege and a Forgotten Civil Rights Movement,” The Atlantic, October 23. Available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2012/10/occupy-wounded-knee-a-71-day-siege-and-a-forgotten-civil-rights-movement/263998/

Crane-Murdoch, S. 2016. “Standing Rock: A New Moment for Native-American Rights,” New Yorker, October 12. Available at: http://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/standing-rock-a-new-moment-for-native-american-rights

Dalrymple, A. 2016. “Pipeline route plan first called for crossing north of Bismarck,” Bismarck Tribune, August 18. Available at: http://bismarcktribune.com/news/state-and-regional/pipeline-route-plan-first-called-for-crossing-north-of-bismarck/article_64d053e4-8a1a-5198-a1dd-498d386c933c.html

Davies, J. G. 2017. “About that black snake prophecy: Fantastic assertion followed by a ceremony,” Native Sun News Today, January 11. Available at: http://www.nativesunnews.today/news/2017-01-11/Voices_of_the_People/About_that_black_snake_prophecy.html

Donnella, L. 2016. “The Standing Rock Resistance Is Unprecedented (It's Also Centuries Old)” NPR, November 22. Available at: http://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2016/11/22/502068751/the-standing-rock-resistance-is-unprecedented-it-s-also-centuries-old

Eicher, A. 2017. “U.S. Army Corps of Engineers: ‘Significant Environmental Damage’ Possible from Dakota Pipeline Protest Camps,” CNS News, February 8. Available at: http://www.cnsnews.com/news/article/andrew-eicher/us-army-corps-engineers-significant-environmental-damage-possible-dakota

Elbein, S. 2016. “Standing Rock Protesters React to Life Under Trump,” Rolling Stone, November 23. Available at: http://www.rollingstone.com/politics/features/standing-rock-protesters-react-to-life-under-trump-w452010

Espinoza, M. 2017. “Standing Rock activist at SRJC: Standing Rock protest energized political resistance,” The Press Democrat, April 3. Available at: http://www.pressdemocrat.com/news/6849598-181/standing-rock-activist-at-srjc?artslide=0

Gambino, L. 2017. “Native Americans take Dakota Access pipeline protest to Washington,” The Guardian, March 10. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/mar/10/native-nations-march-washington-dakota-access-pipeline

Harris, A. 2017. “Sioux Tribe Puts ‘Black Snake Prophecy’ at Center of Dakota Pipeline Battle,” Bloomberg, February 28. Available at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-02-28/tribe-puts-black-snake-prophecy-at-center-of-pipeline-battle

Harris, K., and Gonchar, M. 2016. “Battle Over an Oil Pipeline: Teaching About the Standing Rock Sioux Protests,” New York Times, November 30. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/30/learning/lesson-plans/battle-over-an-oil-pipeline-teaching-about-the-standing-rock-sioux-protests.html

Hughes, B. 2017. “Standing Rock Protesters Leave Gobs of Trash That Could Threaten the River,” MRCtv, February 7. Available at: http://www.mrctv.org/blog/standing-rock-protesters-leave-gobs-trash-could-threaten-river

Lukacs, M. 2016. “Standing Rock is a modern-day Indian war. This time Indians are winning,” The Guardian, December 5. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/true-north/2016/dec/05/standing-rock-is-a-modern-day-indian-war-this-time-indians-are-winning

MacPherson, J. 2016. “Oil pipeline protest turns violent in southern North Dakota,” AP News, September 4. Available at: http://bigstory.ap.org/article/dca1962d120b4b069c0436280ad62bd1/oil-pipeline-protest-turns-violent-southern-north-dakota

McKibben, B. 2016. “A Pipeline Fight and America’s Dark Past,” New Yorker, September 6. Available at: http://www.newyorker.com/news/daily-comment/a-pipeline-fight-and-americas-dark-past

McKibben, B. 2016. “Standing Rock is the civil rights issue of our time – let's act accordingly,” November 29. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/commentisfree/2016/nov/29/standing-rock-civil-rights-act-accordingly

Medina, D. 2016. “Dakota Access Pipeline: What’s Behind the Protests?” NBC News, November 4. Available at: http://www.nbcnews.com/storyline/dakota-pipeline-protests/dakota-access-pipeline-what-s-behind-protests-n676801

Meyer, R. 2016. “The Legal Case for Blocking the Dakota Access Pipeline,” The Atlantic, September 9. Available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2016/09/dapl-dakota-sitting-rock-sioux/499178/

Meyer, R. 2017. “The Standing Rock Sioux Claim ‘Victory and Vindication’ in Court,” The Atlantic, June 14. Available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2017/06/dakota-access-standing-rock-sioux-victory-court/530427/

Moynihan, C. 2016. “Cause of Severe Injury at Pipeline Protest Becomes New Point of Dispute,” New York Times, November 24. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/24/us/dakota-pipeline-sophia-wilansky.html?_r=0

Mufson, S. 2016. “A Dakota pipeline’s last stand,” Washington Post, November 24. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/economy/a-dakota-pipelines-last-stand/2016/11/25/35a5dd32-b02c-11e6-be1c-8cec35b1ad25_story.html?utm_term=.62344e6c967e

Palma, B. 2017. “Standing Rock Activists Clear Trash as Tribes Ask Court to Halt Pipeline,” Snopes, February 10. Available at: http://www.snopes.com/2017/02/10/standing-rock-trash/

Palma, B. 2016. “Standing Rock Protester in Danger of Losing Arm After Police Use Force,” Snopes, November 27. Available at: http://www.snopes.com/2016/11/22/standing-rock-protester-in-danger-of-losing-arm-after-police-use-force/

Palma, B. 2016. “‘This Is Our Ghost Dance.’ Standing Rock Sioux Will Continue Their Dakota Access Pipeline Battle,” Snopes, December 21. Available at: http://www.snopes.com/2016/12/21/ghost-dance-standing-rock-sioux-will-continue-dakota-access-pipeline-battle/

Silva, D. 2016. “Dakota Access Pipeline: More Than 100 Arrested as Protesters Ousted from Camp,” NBC News, October 28. Available at: http://www.nbcnews.com/storyline/dakota-pipeline-protests/dakota-access-pipeline-authorities-start-arresting-protesters-new-camp-n674066

Smith, M. 2017. “Standing Rock Protest Camp, Once Home to Thousands, Is Razed,” New York Times, February 23. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/23/us/standing-rock-protest-dakota-access-pipeline.html

United Nations, Meetings Coverages and Press Releases. 2017. “Governments Must Uphold Commitments, Prevent Reversal of Hard-Won Gains, Speakers Tell Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues,” Economic and Social Council, Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, 16th Session, 3rd Meeting. HR/5323. April 25. Available at: https://www.un.org/press/en/2017/hr5352.doc.htm

Von Oldershausen, S. 2016. “Standing Rock Pipeline Fight Draws Hundreds to North Dakota Plains,” NBC News, October 17. Available at: http://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/standing-rock-pipeline-fight-draws-hundreds-north-dakota-plains-n665956

Wagner, M. 2017. “Dakota Access Pipeline protesters torch campsite before evacuation deadline,” Fox6Now, February 22. Available at: http://fox6now.com/2017/02/22/dakota-access-pipeline-protesters-torch-campsite-before-evacuation-deadline-tmwsp/

© Susannah Crockford 2021

Note

This profile has been provided by Inform, an independent charity providing information on minority and alternative religious and/or spiritual movements. Inform aims to deliver accurate, balanced, and reliable data. It relies on social scientific research methods, primarily the sociology of religion. Inform welcomes feedback, comments, corrections, or further information at inform@kcl.ac.uk.