Introduction

Matthew’s Gospel is one of four canonical Gospels in the Christian New Testament. The text was probably originally written in Greek in the 80s CE in the city of Antioch in Roman Syria. The principal contents are a presentation of the life, teachings, death, and resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth, whom the author proclaims as the Jewish Messiah and as the one who best envisions God’s plan for the people of Israel. Matthew is immersed in apocalyptic discourse. Apocalyptic Jews believed the world was currently under the control of evil cosmic forces but that God would soon intervene in human history to overthrow these forces and establish a divine kingdom, what Matthew calls the ‘kingdom of the heavens’. The final implementation of this new world order was being eagerly anticipated by Matthew’s author and early readers (e.g., 16:28; 24:34,36). Recent scholarship on Matthew has argued that the text is shaped by and responds to a series of crises faced by the author’s community of believers in the late first century, especially Roman imperialism and the power shifts in Judea as a consequence of the Jewish–Roman War of 66–73 CE. To a defeated community on the margins of the empire, Matthew offers hope of God’s ultimate triumph. In order to live through present conditions, Matthew gives practical advice on pertinent ethical issues (chs 5–7), the nature of mission (ch. 10), leadership (16:18–20), issues of theocratic and local governance (18:6–35), opposition to rival groups and authorities (23:1–3), and living through the end times (chs 24–25).

Background

Apocalypticism is a religious current and attitude to history found across many Jewish and Christian texts composed around the beginning of the Christian era. Its characteristic emphases are the imminent end of the world and despair about the conditions of the present. Apocalyptic thought is often essentially dualistic, with all of history divided into two ages: the current age, which is under the rule of evil cosmic powers, and the age to come, in which God will rule supreme (Rowland 1982, 1–2). The text of Matthew assumes that humans are inevitably caught up in this cosmic struggle and that individuals must side either with Jesus (and God) or with Satan.

While Matthew’s Gospel is apocalyptic in outlook, the genre of Matthew is not considered an apocalypse per se but rather a bios, an ancient biography of Greco-Roman form. An ‘apocalypse’, like the book of Revelation, designates a specific literary genre in which an author reveals the divine mysteries of heaven and earth. While Matthew exhibits apocalyptic characteristics, it is not generally classified by scholars as a literary apocalypse. It is also useful to distinguish between ‘apocalyptic eschatology’, which refers to future events such as the final judgment and its aftermath, and ‘apocalyptic discourse’, a broader notion that ‘reflects the concept that God’s judgment is at work in the present time … as well as in the future’ (Wenkel 2020, 2). As we will see, apocalyptic discourse is woven through the entirety of Matthew’s text and is not limited to sections where Jesus explicitly expounds his vision of end-time events (e.g., chs 24–25).

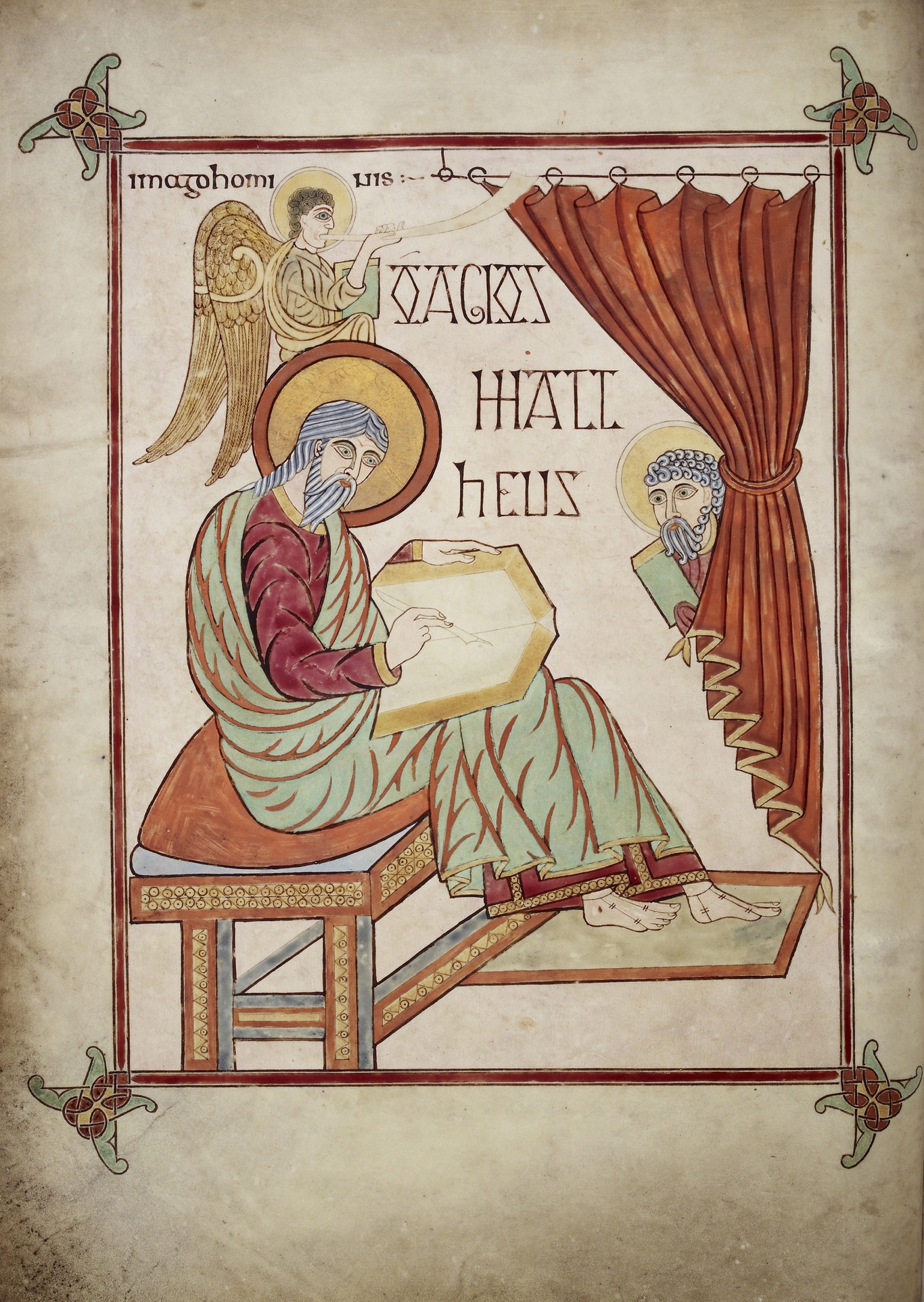

The text of Matthew was originally anonymous, though it has carried the name of Matthew since at least the second century. Matthew the tax collector was one of the original twelve male disciples called by Jesus during his ministry (see Matthew 9:9; 10:3). Although it is possible that the disciple Matthew was an influential figure within the community in which the Gospel originated, apostolic authorship is unlikely given that the text shows a proficiency for Greek and rabbinic training that indicates its author was probably a member of the educated scribal class of Roman Palestine (see e.g., 13:52), though perhaps on the cultural and ideological margins when compared to his scribal counterparts (Orton 1989; Duling 2011).

For most scholars, the Four-Source Hypothesis best explains the literary relationship between the first three Gospels—Matthew, Mark, and Luke—otherwise known as the Synoptic Gospels. According to this explanation, the author of Matthew used two major written sources in composing his Gospel, namely Mark and a hypothetical collection of Jesus’s sayings called Q (from German: Quelle, meaning ‘source’). Q thus refers to common material found in Matthew and Luke but not in Mark. Some scholars continue to argue for the nonexistence of Q (Goodacre 2002). Mark is a primary source for some of Matthew’s apocalyptic content. Material unique to Matthew and Luke is designated M and L respectively.

Most scholars opt for a date of composition during the 80s CE. Matthew implies that the Jerusalem Temple had already been destroyed (e.g., 12:6; 22:7), and so the Gospel must have been written after this event took place in 70 CE. The Gospel of Matthew also appears to be referenced by Ignatius the Bishop of Antioch around 110 CE, so it must have been produced sometime before this date. A window of 80–90 CE seems likely. Antioch, the capital city of the province of Roman Syria, is also favoured as the place of composition for several reasons (Meier 1983; Slee 2003). In addition to Ignatius of Antioch having knowledge of the text, Matthew is the only canonical Gospel to make special reference to Jesus’s activities in Syria (4:24). A minority of scholars have, however, argued instead for a Galilean setting given the many references to that region (4:12; 21:11; 26:32; 28:10; see also e.g., Gale 2005).

Matthew’s Gospel uniquely interprets Jesus through the typology of the Hebrew prophet and lawgiver Moses (Allison 1994). Jesus is characterized as possessing authority on the correct interpretation of the Jewish law over and above rival teachers such as the scribes of Jerusalem (7:28–29; 13:52; cf. 15:1–20). Hence, the text is often divided by commentators according to its five major teaching discourses, separated by the formula ‘when Jesus had finished’ (7:28; 11:1; 13:53; 19:1; 26:1). The first of these is the famous Sermon on the Mount (chs 5–7), a literary construction unique to Matthew that begins with the equally recognizable Beatitudes (5:3–12), a series of eight blessings promising the poor in spirit, the meek, and the persecuted the rewards and riches of heaven in the age to come. The other teaching discourses focus on mission (ch. 10), a series of parables (ch. 13), church organization (ch. 18), and eschatology or final judgment (chs 24–25).

Overview of Apocalyptic Discourse in the Gospel of Matthew

Of the four canonical Gospels, Mark and Matthew have a more pronounced apocalyptic outlook than Luke or John. Matthew in particular amplifies the apocalyptic imagery that is present in Mark, itself written by an anonymous author around the year 70 CE according to most scholars. The theme of judgment saturates Matthew’s discourse. Anders Runesson, in his book Divine Wrath and Salvation in Matthew, has focused on the way Matthew differs significantly from the other Gospels, ‘not only in its fierce emphasis on divine wrath and judgment, unmatched by any other New Testament text with the possible exception of Revelation, but also in its coherent, almost systematic treatment of this theme throughout the narrative’ (Runesson 2016, xiv). Runesson detects three types of judgment in Matthew: first, reward and punishment in this world; second, reward and punishment that are paid in the age to come; and third, the final judgment. He writes, ‘The main outcome of the final judgment … is either what we call salvation, which refers to inclusion in the world to come, or condemnation, which refers to exclusion from life in the coming kingdom’ (Runesson 2016, 44). References to this final judgment recur frequently through the text. Versions of the ominous phrase ‘the weeping and gnashing of teeth’ appear six times to vividly paint the mode of existence for evildoers in the age to come (8:12; 13:42,52; 22:13; 24:52; 25:30). Matthew’s Jesus also frequently gestures towards Gehenna as the location of fiery torment for those who stumble and reject Jesus (5:22,29,30; 18:9).

Another major theme for Matthew is that the rule of God—‘the kingdom of heaven’—is breaking into the world. ‘The kingdom’ appears to refer to an actual kingdom, ruled by God’s anointed one (i.e., the Messiah), in which sovereignty, truth, peace, and justice will be restored. The theme is first encountered in the preaching of Jesus’s forerunner, John the Baptist (3:7–10), who announces that divine judgment has ‘come near’ and that those unprepared will be thrown into a great fire to burn. Jesus himself announces the approaching kingdom in 4:17 at the inauguration of his ministry. Integral to the preaching of John and Jesus is the command to their listeners to ‘repent’ in light of the coming apocalyptic terror (3:2,8,11; 4:18; 11:20,21; 12:41). The ‘cosmic dualism’ between heavenly and earthly kingdoms is a hallmark of Matthew’s apocalyptic substructure. According to Jonathan Pennington (2007), ‘the way Matthew portrays this heavenly kingdom as radically different than the way of the world is reminiscent of the hope-giving function of an apocalyptic orientation toward the future age’ (94, cf. 8, 91–94).

While, as one scholar remarks, ‘from the opening chapter telling of the birth of the Messiah to the closing scene promising his presence until the close of the age, Matthew keeps the readers’ attention fixed upon the apocalyptic consequences of discipleship’ (Cope 1989, 116), there are several key points where apocalyptic imagery is particularly noticeable. A significant focus of Jesus’s first major teaching block, the Sermon on the Mount (chs 5–7), for instance, is entering into this heavenly kingdom. Matthew’s version of the Lord’s Prayer (6:9–13)—probably one of the most familiar passages from this Gospel—invites the full coming of God’s reign in the future, ‘on earth as it is in heaven’ (10b). Its ‘you’ petitions request God’s sovereignty, and its ‘we’ petitions ask for protection and sustenance in the dangerous process of the transition to the new rule of God. Elsewhere in the sermon, we find the well-known binarism uttered by Jesus between the few who ‘enter through the narrow gate … that leads to life’, and the many who enter through the wide gate and easy road that ‘leads to destruction’ (7:12–14; quotations are taken from the New Revised Standard Version). Dualistic thinking is characteristic of Jewish apocalyptic discourse, as is the notion that the faithful will undergo various trials and tribulations before God’s dramatic final intervention (cf. 5:10–12,44; 10:16–33; 13:21; 23:34; 24:9–10). Matthew uses various forms of the verb ‘to persecute’ (dioko/διώκω)—more than any other Gospel—to describe the suffering that faithful followers of Jesus must endure.

Jesus’s parables in chapter 13 also repeatedly allude to this future age and illustrate what life will be like in the kingdom. Drawing on agricultural and fishing imagery that would have been familiar to the mostly rural audience of Jesus’s Galilean ministry, the parables promise abundant harvest and reward but also a decisive final judgment in which the good are separated from the bad. For example, the parable of the wheat and the weeds in 13:24–30, unique to Matthew, compares the heavenly kingdom to someone sowing good seed in their field, only to be followed by an ‘enemy’ sowing weeds among the wheat. At harvest time, the householder instructs the reapers to ‘collect the weeds first and bind them in bundles to be burned’ (13:30). The wheat is gathered and enjoys the heavenly splendours awaiting it in the householder’s barn. The parable appears to contain an allegorical message counselling followers to exhibit patience in the face of those who reject the Gospel, in full confidence that at the culmination of time ‘there will be a separation between the just and unjust along with appropriate rewards and punishments’ (Harrington 2007, 208).

The most heightened apocalyptic imagery in Matthew is found in the extended eschatological discourse of chapters 24 and 25. Here Matthew takes over much of the material from the so-called Little Apocalypse found in Mark 13 and supplements it with parables emphasizing watchfulness in preparation for the coming wrath in the transition to the new age. Paul Foster observes that Matthew’s eschatological concern is further revealed in that ‘he is the only one of the canonical Gospel writers to use the term παρουσία [parousia], and he does so to designate the coming of Jesus at the end of the age’ (Foster 2020, 78). The final judgment is outlined in detail in 25:31–46. Here Jesus speaks of his returning ‘in all his glory’, accompanied by angels gathering the righteous with the sound of a trumpet (24:31) and sitting on the throne to judge all the nations gathered before him. The passage includes a figurative story about a shepherd separating his herd into sheep on his right and goats on his left. The shepherd then morphs into a king and says those on his right hand will inherit the kingdom while those on his left are doomed to depart ‘into the eternal fire prepared for the devil and his angels’ (25:41b).

At the climax of Matthew’s narrative, the events of Jesus’s death and resurrection are laden with apocalyptic imagery that implies their cosmic significance. During Jesus’s final moments on a Roman crucifix, Matthew suggests that ‘darkness came over the whole land’ (27:45). At the exact moment of Jesus’s death, the curtain of the Jerusalem Temple is torn in half and there is an earthquake in which rocks are split and tombs are opened. The imagery evokes the mention of earthquakes as one of the signs of the end in 24:7 but also gestures towards the destruction of the Temple and its replacement with Jesus as God’s reigning authority (cf. 12:6). Matthew describes the bodies of dead saints coming back to life and roaming the holy city of Jerusalem in the days following Jesus’s resurrection (27:52–53). On this passage, N. T. Wright reasons that ‘some stories are so odd that they may just have happened’ (Wright 2003, 636). However, there are several social and historical factors that may have generated such ideas, given the often eccentric symbolism of apocalyptic discourse. According to some commentators, at least, the raising of ‘many bodies’ at Jesus’s death motions ‘an inbreaking of God’s power signifying that the last times have begun and the judgment has been inaugurated’ (Brown 1994, 1126).

In the final pericope of Matthew’s Gospel, the resurrected Jesus appears in all his glory to his eleven remaining disciples (Judas having committed suicide in 27:5) and declares that he has been given ‘all authority in heaven and on earth’, that they should make disciples of all nations, and that he will be with them until ‘the end of the age’ (28:18–20).

Social and Historical Reasons for Matthew’s Apocalypticism

To what extent is the apocalyptic worldview of Matthew simply an accurate reflection of the teaching of Jesus? Put otherwise, is the Gospel’s characterization of Jesus as one who warned incessantly of divine judgment and radical societal transformation from one age to the next historically accurate? A number of contemporary scholars (although certainly not all) argue for the view that the historical Jesus was an apocalyptic prophet (see e.g., Wright 1996; Ehrman 1999; Fredriksen 1999; Allison 2010). Even so, such a view leaves several further questions unanswered. Why, for instance, does Matthew appear to build on and accentuate Mark’s apocalyptic discourse? Relatedly, why is the apocalyptic outlook of Luke and/or John far more muted or absent altogether? In order to more fully appreciate the reasons for Matthew’s apocalyptic outlook, we need to look at some of the broader social and historical factors that preceded the text’s composition in the 80s ce.

Scholars typically identify the devastating assertion of Roman power during the Jewish Revolt (66–73 CE), resulting in the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple in 70 ce, as a major influence on Matthew’s apocalyptic outlook. During the Revolt, Antioch—the likely place of the Gospel’s composition—had been a staging ground for the Roman armies coming to invade Judea. The rise of revolutionary militias engaging in battle with Romans would have been regarded both at the time and in the decades following as electrifying events for many Jews. According to Neil Faulkner (2002), ‘the best of the militiamen imagined this time to be the End of Days, and these to be the battles of the Apocalypse’ (132). The famines, earthquakes, wars, and rumours of wars described in Matthew’s eschatological discourse (ch. 24) were thus reflective of the actual experiences of the Matthean audience in the late first century (Wainwright 2017, 191).

The Revolt also had momentous implications for the shape of Jewish identity and society thereafter, and the events and their aftermath prompted much theological reflection on the immediate past, including the circumstances that led up to the capture of Jerusalem. Without the governing institution of the Temple, and a scattered and defeated population, ‘formative Judaism’ was thrown into an identity crisis of sorts, with different groups among the scribal elite competing to define a new understanding of what would constitute ‘authentic’ Jewish identity and practice from here on out (Overman 1990). Outside the New Testament, there are at least three extant ‘apocalypses’ from around the turn of the second century that have similar issues in their sights, chiefly, 4 Ezra, 2 Baruch, and the Apocalypse of Abraham. As in Matthew, a primary concern is theodicy: Why did the Jewish God permit the destruction of his own Holy Temple (Esler 2005, 20; cf. Stone 1981)?

According to David C. Sim, whose 1996 monograph Apocalyptic Eschatology in the Gospel of Matthew remains the definitive historical–critical study on the topic, the primary function of Matthew’s apocalyptic discourse is to confront and combat these crises faced by the author’s community. Matthew vehemently discredits the respective worldviews of competing Jewish groups, in addition to the law-free wing of Christianity represented most prominently by Paul, to legitimate and reinforce the beliefs, outlook, and hopes of his own group. However, the Matthean community sees itself in conflict not with human groups but with powerful demonic forces. For Sim, ‘the current situation has not happened merely by historical chance in the aftermath of the Jewish war … On the contrary, the present plight of the ekklesia [church/assembly] is an essential part of God’s predetermined historical and eschatological plan’ (Sim 1996, 225). Drawing on a well-established pattern from the prophetic tradition, Matthew’s text reasons that the Roman destruction of Jerusalem and its Temple was a punishment on the rulers of Galilee and Judea for rejecting Jesus (22:1–10). However, Rome itself is also under God’s judgment, and Matthew fantasizes about Jesus’s return to judge the nations and fully implement God’s reign on earth.

Thus, it seems the source of Matthew’s apocalyptic outlook may be a combination of Jesus’s own influence alongside the social and religious crises that pervaded Matthew’s context. While some scholars argue that the historical Jesus quite likely ‘predicted’ the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple during his own lifetime, given the tradition is spread through multiple sources (Ehrman 1999, 157; Matthew 24:1–2; cf. Mark 13:1–2; Luke 21:5–6; John 2:19), in composing his Gospel Matthew may have seized upon this prediction as an example of ‘prophecy fulfilled’ and reinterpreted his sources accordingly. This would present another example of Matthew intensifying and reshaping apocalyptic influences on his writing, as is already evident from his reworking of Mark. Ultimately, Matthew presents the theological resolution to the absence of a physical Temple in the person of Jesus the Messiah and in the coming reign of God. Through this central motif the text constructs a differentiated identity and societal vision that paves a way forward for Jews without the need for the Temple.

A related social factor that may have generated Matthew’s apocalyptic attitude is that such views typically went hand in hand with opposition to the ruling powers. In a subsequent publication, Sim (2005) notes that ‘Matthew inextricably connects Satan and the Roman Empire. In the context of the cosmic battle between God and Satan, the Romans have opted to throw in their lot with the latter’ (93). So-called anti-imperial readings of Matthew have thus become increasingly popular over the past few decades and provide another avenue for exploring the text’s heightened apocalyptic imagery. For example, the Greek word typically translated in English Bibles as ‘kingdom’ (basileia/βασιλεία) could alternatively be translated as ‘empire’. Any reader or hearer of the text in the first century would accordingly have associated the coming ‘empire’ of the heavens proclaimed by Jesus as the intended replacement for Caesar’s empire. While Rome itself is never explicitly mentioned within the text, and the emperor receives only brief mention in 21:15–22, several scholars suggest that the impact of Roman power on the early Jewish Christian movement was integral to the composition and early reception of the Gospel.

The most active scholar in developing an ‘anti-imperial’ approach to Matthew has been Warren Carter, who has written both a monograph, appropriately titled Matthew and Empire (2001), and a commentary critically engaging the Gospel from a religious and sociopolitical perspective (Carter 2000; cf. Riches and Sim 2005). For Carter, Matthew’s story of Jesus functions as a ‘counternarrative’ or work of resistance literature. Written for a largely Jewish religious group, ‘it “stands and/or speaks over against” the status quo dominated by Roman imperial and synagogal control’. It resists these structures by offering an alternative worldview and community, thereby affirming ‘a way of life marginal to the dominant structures’ of those living in the aftermath of Rome’s devastating conquest of Judea (Carter 2000, 1). Carter embraces a hermeneutic of ‘marginality’ to argue that the Gospel negotiates a marginal identity for the community of disciples around Jesus. The cosmic struggle between the two ages in Jewish apocalyptic discourse is explored principally through the clash between Roman imperial theology and Jewish theology and Messianism, as it is interpreted in relation to Jesus. Carter observes that ‘in Jesus’ ministry, the new age marked by God’s reign or empire is beginning to dawn. At Jesus’ return, it will be established in full through judgment and vindication’ (Carter 2000, 10). Matthew’s presentation of Jesus as Son of God and inaugurator of the heavenly kingdom contrasts with the dominant Roman imperial view that the emperors of Rome were themselves chosen representatives of the gods, ‘notably Jupiter’s agent, with the tasks of manifesting the gods’ rule, presence, will, and blessings among human beings’ (Carter 2001, 33–34).

Such approaches to Matthew have not been without their critics. To begin with, it is important to note that Matthew is the literary product of an urban-based, semi-elite scribal class; as such, although the author writes about the lives of ordinary rural peasants, artisans, and fishermen, he does so through the eyes of his own relatively elite bureaucratic and political interests. Indeed, ‘scribal texts, including those classified as “apocalyptic”, are thus not good guides to the perspective and attitudes of ordinary people’ (Horsley 2010, 200). This ought to temper the extent to which we might regard ancient texts like the Gospel of Matthew as so-called resistance literature, even if they did originate from the cultural or ideological margins of the scribal class. Although we should be careful to avoid excluding the possibility of apocalypticism from below, there nonetheless remains some truth to Randall W. Reed’s (2010) claim that ‘it is not the struggling under-classes who rebel against the imperial boot; rather, apocalypticism is an elite response to political displacement’ (53). Furthermore, scholars applying feminist and postcolonial approaches have frequently pointed out that the Gospel of Matthew mimics the rhetoric of empire in order to negate it, but, along with other so-called anti-imperial texts of the New Testament, somewhat ironically ends up laying the groundwork for its own brand of imperial rule (Moore 2006; Schüssler Fiorenza 2007; cf. Carter 2009; Myles 2016). In the promised new world order, existing sociopolitical arrangements remain; however, they are now under the control of a different Lord of lords—namely, God and his co-regent, Jesus. One scholar has even translated the basileia (kingdom) of the heavens proclaimed by Jesus as the ‘Dictatorship of God’ to highlight the ‘theocratic’ dimensions that are sometimes underemphasized by modern liberal and religious readers (Crossley 2015).

Whether or not we classify Matthew as ‘resistance literature’, the text nonetheless pronounces severe judgment on the existing social and political orders of its day. As we have seen, apocalyptic discourse is the primary vehicle through which the text communicates this uncompromising vision of radical societal change. For its earliest readers, then, Matthew’s apocalyptic promise of a new age ruled by God presumably provided at least some hope and encouragement for those who earnestly believed themselves to be living through the end of days.

References

Allison, Dale C. 1994. The New Moses: A Matthean Typology. Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress.

Allison, Dale C. 2010. Constructing Jesus: Memory, Imagination, and History. Grand Rapids, CA: Baker Academic.

Brown, Raymond E. 1994. The Death of the Messiah: From Gethsemane to the Grave: A Commentary on the Passion Narratives in the Four Gospels, vol. 2. New York: Doubleday.

Carter, Warren. 2000. Matthew and the Margins: A Sociopolitical and Religious Reading. Maryknoll, Australia: Orbis.

Carter, Warren. 2001. Matthew and Empire: Initial Explorations. Harrisburg, PA: Trinity Press International.

Carter, Warren. 2009. ‘The Gospel of Matthew.’ In A Postcolonial Commentary on the New Testament Writings, edited by Fernando F. Segovia and R. S. Sugirtharajah, 69–104. London: T&T Clark.

Cope, O. Lamar. 1989. ‘“To the Close of the Age”: The Role of Apocalyptic Thought in the Gospel of Matthew.’ In Apocalyptic and the New Testament, edited by Joel Marcus and Marion L. Soards, 113–24. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press.

Crossley, James G. 2015. Jesus and the Chaos of History: Redirecting the Quest for the Historical Jesus. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Duling, Dennis. 2011. A Marginal Scribe: Studies in the Gospel of Matthew in a Social-Scientific Perspective. Eugene, OR: Cascade.

Ehrman, Bart D. 1999. Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Esler, Philip F. 2005. ‘Rome in Apocalyptic and Rabbinic Literature.’ In The Gospel of Matthew in Its Roman Imperial Context, edited by John Riches and David C. Sim, 9–33. London: T&T Clark.

Faulkner, Neil. 2002. Apocalypse: The Great Jewish Revolt Against Rome AD 66–73. Stroud: Amberley.

Foster, Paul. 2020. ‘The Eschatology of the Gospel of Matthew.’ In ‘To Recover What Has Been Lost’: Essays on Eschatology, Intertextuality, and Reception History in Honor of Dale C. Allison Jr., edited by Tucker S. Ferda, Daniel Frayer-Griggs, and Nathan C. Johnson, 77–103. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill.

Fredriksen, Paula. 1999. Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews: A Jewish Life and the Emergence of Christianity. New York: Vintage.

Gale, Aaron. 2005. Redefining Ancient Borders: The Jewish Scribal Framework of Matthew’s Gospel. New York: T&T Clark.

Goodacre, Mark. 2002. The Case Against Q: Studies in Markan Priority and the Synoptic Problem. Harrisburg, PA: Trinity Press International.

Harrington, Daniel J. 2007. The Gospel of Matthew. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press.

Horsley, Richard A. 2010. Revolt of the Scribes: Resistance and Apocalyptic Origins. Minneapolis: Fortress Press.

Meier, John P. 1983. ‘Antioch.’ In Antioch and Rome: New Testament Cradles of Catholic Christianity, edited by Raymond E. Brown and John P. Meier, 12–86. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press.

Moore, Stephen D. 2006. Empire and Apocalypse: Postcolonialism and the New Testament. Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix.

Myles, Robert J. 2016. ‘The Fetish for a Subversive Jesus.’ Journal for the Study of the Historical Jesus 14 (1): 52–70.

Orton, David E. 1989. The Understanding Scribe: Matthew and the Apocalyptic Ideal. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press.

Overman, J. Andrew. 1990. Matthew’s Gospel and Formative Judaism: The Social World of the Matthean Community. Minneapolis: Fortress Press.

Pennington, Jonathan T. 2007. Heaven and Earth in the Gospel of Matthew. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill.

Reed, Randall W. 2010. A Clash of Ideologies: Marxism, Liberation Theology, and Apocalypticism in New Testament Studies. Eugene, OR: Pickwick.

Riches, John, and David C. Sim, eds. 2005. The Gospel of Matthew in Its Roman Imperial Context. London: T&T Clark.

Rowland, Christopher. 1982. The Open Heaven: A Study of Apocalyptic in Judaism and Early Christianity. London: SPCK.

Runesson, Anders. 2016. Divine Wrath and Salvation in Matthew: The Narrative World of the First Gospel. Minneapolis: Fortress.

Schüssler Fiorenza, Elisabeth. 2007. The Power of the Word: Scripture and the Rhetoric of Empire. Minneapolis: Fortress.

Sim, David C. 1996. Apocalyptic Eschatology in the Gospel of Matthew. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sim, David C. 2005. ‘Rome in Matthew’s Eschatology.’ In The Gospel of Matthew in Its Roman Imperial Context, edited by John Riches and David C. Sim, 91–106. London: T&T Clark.

Slee, Michelle. 2003. The Church in Antioch in the First Century: Communion and Conflict. London: T&T Clark.

Stone, M. E. 1981. ‘Reactions to the Destruction of the Second Temple: Theology, Perception and Conversion.’ Journal for the Study of Judaism, 12 (2): 195–204.

Wainwright, Elaine M. 2017. Habitat, Human, and Holy: An Eco-Rhetorical Reading of the Gospel of Matthew. Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix.

Wenkel, David H. 2020. ‘The Gospel of Matthew and Apocalyptic Discourse.’ Expository Times, December, 1–12.

Wright, N. T. 1996. Jesus and the Victory of God. Minneapolis: Fortress.

Wright, N. T. 2003. The Resurrection of the Son of God. Minneapolis: Fortress.

© Robert J. Myles 2021