Summary of movement

The Sadrist Movement—named after prominent clerics from the al-Sadr family—emerged in Iraq in the 1990s amid the Shia Muslim uprising against President Saddam Hussein after his defeat in the Gulf War. A product of decades of suppression of the Shia population under the Sunni-led Baath Party, the revolt was violently crushed by Saddam. The US invasion of 2003 and the overthrow of Saddam resulted in the formation of the anti-US Mahdi Army, the Sadrist Movement’s militia wing. The Sadrists, however, set violence aside when they participated in the general election of 2005 as part of a wider coalition of Shia parties. The Mahdi Army was disbanded in 2008, only to be revived as the Peace Companies around 2014 to fight against the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS), the Sunni militant jihadist group. Since 2003, the Sadrist Movement—in its militant and political incarnations—has been led by Muqtada al-Sadr, whose persona and public statements are often imbued with messianism and millenarianism.

History/Origins

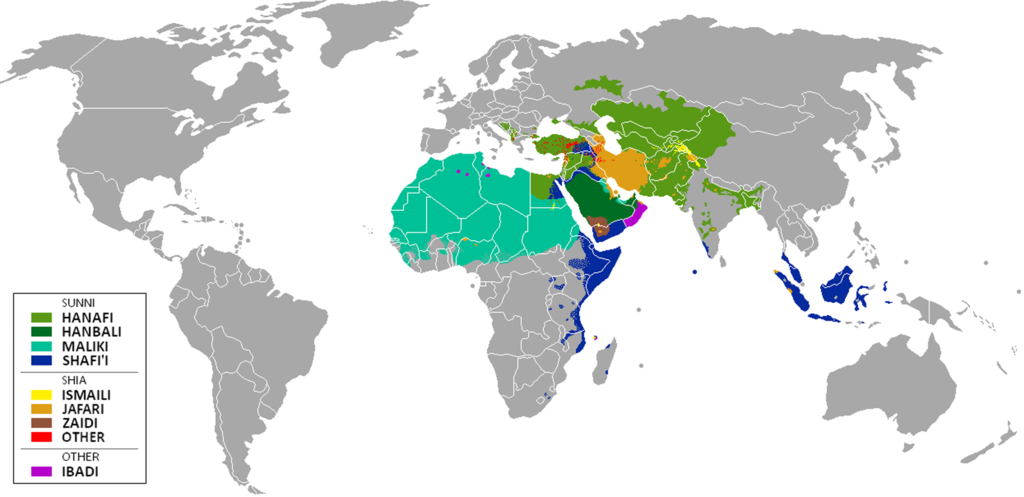

Although Shias constitute no more than 15 per cent of the global population of Muslims, they form the majority or a significant minority in some countries. Shias constitute 90 to 95 per cent of the total Muslim population in Iran (which is 99.4 per cent Muslim) and around 65 per cent in Iraq (96.4 per cent Muslim). Historically, Shia communities and clerics tended to congregate in areas where the authority of the Sunni-led Caliphate was weak. Shia ulama (religious scholars) also found a foothold in territories under the rule of Shia dynasties, such as the Buyids (who ruled Baghdad between 945 and 1055) and the Safavids (1501–1722) who made Shiism Iran’s state religion (Louer, 2012, 6–7).

There are three main branches of Shiism, based on their belief about the legitimacy of particular individual imams (spiritual-political leaders who succeeded the Prophet Muhammad). The Fivers believe in the legitimacy of Zayd ibn Ali (d. 740) as the fifth imam, as opposed to Muhammad al-Baqir (d. 733)—which is why they are also known as Zaydis. The Seveners, also known as Ismailis, believe that the imamate passed to Ismail ibn Jafar (d. 762) as opposed to Musa al-Kazim (d. 799). The vast majority of Shias are Twelvers, or Ithna Ashari, who believe that the imamate continued until the twelfth imam, Muhammad al-Muntazar, also known as the Hidden Imam, went into occultation. They believe that he will return one day as the Mahdi (a messianic figure) to lead the forces of good against evil in one final apocalyptic battle in which the Imam’s enemies will be vanquished (Momen, 1985).

The majority of contemporary Shia political movements were founded and led by clerics, even though some anti-clerical strands do exist. The establishment of the Iraqi nation-state in 1921, in particular, significantly transformed the nature of Shia religious institutions (Louer 2012, 10). Forming an alliance with tribal chiefs, Shia ulama raised an army and led a revolt to drive the British out of Mesopotamia. The ulama were unsuccessful and many were cast out by the British instead, which fragmented the centres of Shia religious authority. Many fled Najaf in Iraq—the centre of Shiism’s most prestigious seminaries—to settle in Qom in Iran. In the 1960s, the socialist, Sunni-dominated but nominally secular Baath Party took power and started suppressing Shia religious institutions. This, and the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran, contributed to the rise of Qom as the principal centre for clerical training. Qom became the Shia world’s scholarly centre while Najaf remained its centre of religious authority (Louer 2012, 11).

Against this background, clerics from the al-Sadr family were pivotal in the development of political Shiism. Muhammad al-Sadr played a central role in the 1920 revolution and served as prime minister of Iraq in 1948. In the late 1950s, Mohammed Baqir al-Sadr was a key figure in the establishment of the Shia world’s first contemporary political party, al-Dawa, in Najaf. In Lebanon in the 1960s, Musa al-Sadr’s Movement of the Deprived reinterpreted some core Shia rituals, which were suffused with fatalism, into expressions of political rebellion (Louer 2012, 12, 15).

Shia political movements were often violently suppressed in Sunni-led regimes. The Iraqi Baathist administration was particularly vicious in the 1970s, resulting in movements like al-Dawa becoming more militant. Saddam’s forces routinely arrested thousands of al-Dawa members and executed hundreds—Baqir al-Sadr was put to death in 1980 (Cockburn 2008, 40–43). Musa al-Sadr ‘vanished’ while travelling in Libya in 1978—he was probably murdered by the regime of Muammar al-Gaddafi (Louer 2012, 47). The circumstances of Musa’s disappearance aroused messianic and millenarian sentiments amongst his followers, who drew parallels between this incident and the Twelver Shia belief in the occultation of the Hidden Imam.

The Iranian revolution triggered a seismic shift in the geopolitics of the Middle East. Sunni-led Arab regimes worried about a potential domino effect while the new Iranian leadership made no secret of its desire to export the revolution (Louer 2012, 51). For example, in 1982, Iran set up Hezbollah (the Party of God) to oppose US and Israeli forces in the midst of the Lebanese civil war. In the same year, Iran also initiated the formation of the Supreme Council for Islamic Revolution in Iraq (SCIRI)—now known as the Supreme Islamic Council in Iraq (Louer 2012, 65). Some Shia factions from Iraq also actively began to support the new Iranian regime of their own accord, such as the followers of Mohammed Shirazi (Louer 2012, 52). However, Shirazi eventually became disillusioned with the regime’s brutal crackdown of ‘counter-revolutionaries’ (Louer 2012, 72). On a wider level, Shia political movements became polarised between those that supported Iran and its mode of government and those that rejected it.

After Saddam declared war on Iran in 1980, the Baathists crushed Shia movements even more violently, which only cemented Iran’s status as the centre of global Shiism. Yet despite the sectarian nature of the war, the Iraqi army—composed mainly of Shias—did not mutiny en masse, suggesting that many Iraqi Shia fighters put national loyalty before sectarian identity (Cockburn 2008, 46). During the war, Saddam was supported by the US, the Soviet Union, Western European powers and most of the Arab world (except Syria).

When it ended in 1988, the war had devastated both countries. However, while Iran began adopting a more circumspect and pragmatic foreign policy, Iraq continued being selectively aggressive towards its neighbours. In 1990, an escalating border dispute about an oil field led to Saddam’s invasion of Kuwait in a war that was also driven by Iraq’s historical claims over the region (BBC 1990). The Iraqi army’s defeat in 1991 was swiftly followed by a Shia uprising within the country—the Shaaban Intifada (Cockburn 2008, 55). Shaaban is the Muslim month during which Twelver Shias celebrate the anniversary of the Mahdi’s birth.

Saddam quickly crushed the uprising and, in 1992, installed Mohammed Sadiq al-Sadr—a distant cousin of Baqir’s (who had been executed in 1980)—as the leader of the Shia community. Although he appeared to cooperate with Saddam’s regime after 1992, Sadiq had a history of openly criticising quietist and pacifist Shia clerics in the 1980s and was imprisoned alongside other vocal clerics during the 1991 uprising. Meanwhile, US sanctions imposed after 1990 impoverished Iraq and hit its Shia population especially badly. Under these conditions, Sadiq’s leadership became more appealing, especially to disgruntled Shia youth, thus marking the growth of the Sadrist Movement.

From 1997, Sadiq’s preaching became increasingly confrontational and the regime began restricting his activities (Cockburn 2008, 88). Secret intelligence officers infiltrated his religious circle. Yet his Shia opponents accused him of being a pro-regime collaborator, even after he and his two elder sons were ambushed and killed by security forces in Najaf in 1999. The leadership of the Sadrist Movement eventually fell to Sadiq’s fourth son, Muqtada, who was 25 when his father and elder brothers were assassinated.

After 2003, Muqtada’s influence grew exponentially, especially in the wake of intra-Shia rivalries unleashed by the US military invasion and the downfall of Saddam. Muqtada established his base in the Baghdad suburb of Al-Thawra or Saddam City, which he renamed Sadr City in honour of his father (Cockburn 2008, 112). Muqtada was scathing about Shia leaders who had collaborated with the former regime or with Iran, and was deeply opposed to the US occupation of Iraq. In being both anti-US and ambivalent about Iran, Muqtada’s Sadrist Movement was therefore unique amongst other Iraqi Shia movements, which were less overtly anti-US and often warmer towards Iran. Muqtada formed the Mahdi Army, a militia which launched an anti-US insurrection in 2004. US forces managed to contain the insurrection and Muqtada suffered heavy military losses (Louer 2012, 92).

Muqtada then abandoned violence and regained national influence via the political process. The Sadrist Movement became a key partner in the Shia coalition—the United Iraqi Alliance—that contested the 2005 general election. The UIA was victorious, and the Sadrists gained more than 10 per cent of seats in parliament and control over the transportation and health ministries (Godwin 2012, 448). However, when sectarian violence between Sunnis and Shias flared up in 2006, Muqtada reactivated the Mahdi Army. In response to the Sunni insurgency, President George W Bush increased the number of US troops in Iraq in 2007, which also undermined the Mahdi Army’s influence yet again. Muqtada then announced a ceasefire and retreated to Qom in Iran to pursue further religious education.

The Mahdi Army was officially disbanded in 2008. In 2010, Muqtada called on his supporters to participate in the general election and to back candidates who were calling for a complete withdrawal of US troops. In 2011, Muqtada returned to Najaf but then announced his exit from politics in 2014 (Plebani 2014, 7). Later that year, he revived the Mahdi Army under a different name—the Peace Companies—to fight against ISIS, the Sunni jihadist militia. In 2016, Muqtada led mass protests against the administration of Haider al-Abadi, the Iraqi prime minister since 2014, accusing the government of corruption and failing to carry out crucial reforms (Arraf 2016).

Underneath its political pragmatism and militant tendencies, the Sadrist Movement draws upon and innovates the basic narrative in Islam about the end times, common to both Sunni and Shia traditions. Basically, amid a period of turmoil and violence, a messianic figure called the Mahdi will appear. A war between Muslims and unbelievers will ensue that will also unleash the Dajjal. The Dajjal will be victorious but will eventually be defeated by Jesus—who did not die on the cross but was taken up to Heaven and will return—with the help of the Mahdi. The hordes of Yajuj and Majuj (Gog and Magog) will then attack but Jesus will vanquish them, too. He will then reign as caliph and a period of unprecedented prosperity will follow when the world will turn to Islam. Jesus and the Mahdi will then die natural deaths, followed by a final period of chaos before the end of the world (Beattie 2013, 92).

Details of the exact timings and locations for these events remain ambiguous, however, and have been subjected to different sectarian interpretations throughout Islamic history. Shia traditions have especially emphasised apocalyptic and millenarian beliefs about the return of the Hidden Imam as the Mahdi (Filiu 2011, 141). When in power, however, Shia authorities have historically tried to discourage messianic speculation amongst the general population because of its destabilising potential. This has not prevented periodic outbreaks of messianism amongst Shias which, in the twentieth century, took on increasingly political dimensions.

At the dawn of the twenty-first century, the US-led invasion of Iraq catalysed new expressions of apocalypticism, millenarianism and messianism amongst Sunnis and Shias in the Middle East. In political Shiism, especially, these beliefs were not only directed at foreign or Sunni opponents, but also reflected intra-Shia tensions between quietists and militants and their conflicting geopolitical loyalties within the region.

Beliefs

The Sadrist Movement, like so many other contemporary Shia political groupings, draws upon some core beliefs and historical turning points in Shiism.

Shiism itself began as a political movement that gradually developed its own doctrines and practices that set it apart from the Sunni majority in the Muslim world. In brief, the Shias are those who believed that the Prophet Muhammad’s leadership should have gone to his cousin and son-in-law, Ali ibn Abi Talib, and his descendants. Those who accepted the succession of Muhammad’s companions and upheld the majoritarian leadership of the Muslim community became known as Sunnis.

After Muhammad’s death, the religious and political leadership of the nascent Muslim community was taken over by four of his companions in succession. In Sunnism, they are commonly referred to as the Khulafa Rashidun (Rightly Guided Caliphs)—Abu Bakr (r. 632–634), Umar (r. 634–644), Uthman (r. 644–656) and Ali (r. 656–661). Early Muslim sources note that Uthman’s rule was marked by nepotism in favour of his relatives, the Umayyads. After he was assassinated, Ali took on the leadership of the community, albeit reluctantly, amid staunch opposition from the Umayyads.

After Ali was assassinated in 661, the community became split between factions that wanted Ali’s death avenged and those which accepted the leadership of Muawiyah (r. 661–680), who established the dynastic Umayyad caliphate based in Damascus. After Muawiyah’s death, the Shias of Kufa, in modern-day Iraq, invited Husayn (Ali’s second son and Muhammad’s grandson) to become caliph. The Iraqi governor stopped Husayn’s caravan at Karbala, however, and massacred him and many of his family members. This incident contributed to the gradual growth of specific Shia doctrines and beliefs, especially as the Shias then became a minority that was often persecuted by Sunni-led regimes.

The Sadrist Movement draws upon this history to build its claims of legitimacy and to agitate for social reforms. Prior to the emergence of the Movement in the 1990s, Baqir al-Sadr (executed in 1980 and the cousin of Muqtada’s father) had written a popular essay/booklet in 1977 which attempted to explain the ‘miracle’ of the longevity of the Hidden Imam or Mahdi. According to Baqir, although the Mahdi was born in 869, he was alive and living among us, and is waiting for the right moment to reappear to help victims of oppression (Filiu 2011, 142). For Baqir, a living, thousand-year-old Mahdi was plausible because the Qur’an contained a precedent—the Prophet Noah was reported to have lived for 950 years. Baqir’s justification for a flesh-and-blood, living Mahdi gained ground in neighbouring Shia communities, especially in Lebanon (Filiu 2011, 145).

In the following decades, the legacy of Baqir and his successor Sadiq—Muqtada’s father, who was also assassinated in 1998—endowed this version of Mahdism with a populist appeal that became increasingly hostile towards the Iraqi regime and the US. After the US-led invasion of 2003, this helped Muqtada’s newly launched Mahdi Army to swell its ranks to tens of thousands of members swiftly. The Army interpreted its militant activity as a means of carrying out the Hidden Imam’s imperative to bring about justice (Filiu 2011, 148).

Practices

On the whole, Shiism and Sunnism share core similarities in terms of accepted beliefs and ritual observance. Shia interpretations of these observances are often more infused with themes of suffering and martyrdom. Sunnis and Shias differ more markedly in their rulings on social relations and transactions, for example regarding marriage, divorce and inheritance. According to Moojan Momen (1985), a scholar of Bahaism who has also written about Shiism, some of Twelver Shiism’s more distinctive doctrines and practices include:

- The doctrine of the imamate, according to which the rightful leadership of the community of Muslims should have passed from Muhammad to Ali and their direct descendants. The belief in the occultation of the twelfth imam, or the Hidden Imam, also makes the imamate a more esoteric concept compared to the caliphate—the traditional Sunni model of political government.

- The congregational Friday prayer does not hold the same significance for Shias as it does for Sunnis, since the Hidden Imam—the true prayer leader—is in occultation. This changed, however, after the 1979 Iranian Revolution.

- Unlike Sunnis, the Shias have developed elaborate pilgrimage rituals to shrines of their imams (ziyarat) in addition to the pilgrimage to Mecca (haj).

- Shia jurisprudence allows for temporary marriage (muta), which Sunnis consider forbidden and akin to prostitution.

- Because of the persecution that Shias have historically faced, they also consider it lawful to practice taqiyyah (concealing or dissimulating true faith under life-threatening or risky conditions).

- Shias have much stricter rules on divorce compared to Sunnis. According to Shia jurisprudence, the husband is forbidden to proclaim divorce in anger or in drunkenness. Additionally, the pronouncement must be made explicitly in the presence of two witnesses.

- Shias also have less male-centric inheritance laws compared to Sunnis, which might have something to do with the important position held by Fatimah (Ali’s wife and the Prophet’s daughter).

Modern Developments

The central doctrine of the imamate means that Twelver Shiism is also more explicitly clerical and hierarchical compared to Sunnism. This has translated into particular relationships between Shia communities and state authorities over the centuries. A major turning point was the Safavid Empire’s (1501–1736) designation of Shiism as the state religion, the significance of which is comparable to the Protestant Reformation in Europe (Cole 2002, 3). It was during Safavid rule in Persia (modern-day Iran) that the Shia clerical hierarchy became more institutionalised. Titles that are employed by high-ranking clerics today, such as ayatollah (sign of God) and hujjat al-islam (proof of Islam), emerged during this period.

During the Safavid era, however, the Akhbari or more literalist strand of theology predominated. Akhbaris held that because the Hidden Imam was in occultation, some religious practices could be relaxed or allowed to lapse. In the post-Safavid era, the Usuli or rationalist strand of theology, which was more pro-clerical, came to dominate Twelver Shiism. Usulis held that learned Shia scholars, or ulama, could stand in proxy for the Hidden Imam while awaiting his return. They could thus authorise state leaders to undertake obligations such as collecting taxes, appointing prayer leaders and leading defensive jihad (holy war) against invading enemies (Cole 2002, 10). In the nineteenth century, the jurist Murtada al-Ansari (1781–1864) developed the doctrine of marjaiyya al-taqlid (model or source of imitation), which effectively created the position of a Grand Ayatollah who could make decisions on behalf of lay Shias or clerics with lesser credentials (Louer 2012, 10).

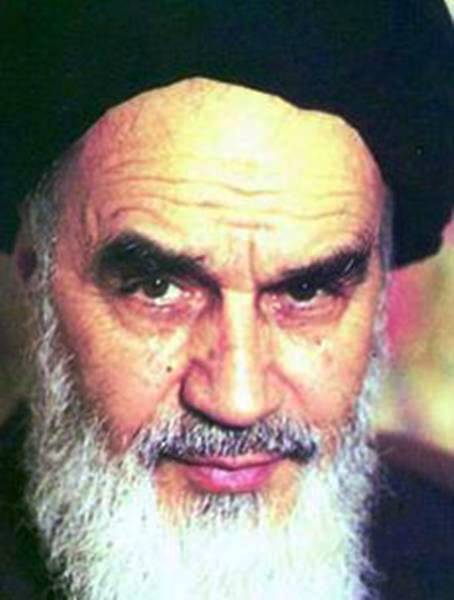

This combination of developments paved the way for a recasting of the traditional themes of martyrdom, messianism and millenarianism, resulting in more militant, revolutionary expressions of Shiism in the twentieth century. Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini, for example, built upon the concept of marjaiyya al-taqlid and Usuli thought to argue for a state that was led by clerics—the wilayat al-faqih (guardianship or governance of the jurist). In doing this, Khomeini turned post-occultation Twelver Shia theology into a revolutionary movement that successfully overthrew the secular Pahlavi monarchy in 1979 (Cole 2002, 10). The Sadrist Movement’s combination of revolutionary zeal and political pragmatism needs to be understood within this historical context.

Millennial Beliefs

For Shias, the messianic expectation of the return of the Hidden Imam has been a fundamental element of doctrine since the ninth century (Louer 2012, 135). However, the development of the Shia clerical hierarchy, especially since the Safavid era, effectively diluted millenarian expectations within a growing religious bureaucracy. Outbreaks of millenarianism have since occurred, but these have often been anti-clerical and were often fiercely resisted by the clergy and the state. One prominent example was the cleric-led suppression of the ‘babist’ movement in nineteenth century Iran, which gave rise to a new religion, Bahaism.

The Sadrist Movement in Iraq is not entirely anti-clerical. In the 1990s, however, Sadiq al-Sadr’s rhetoric depended upon drastic reinterpretations of classical Shia doctrines as a means to establish his legitimacy. This was after his appointment by Saddam Hussein as the state-approved marja (source of imitation), amid hostility by those who supported rival clerics such as Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani (Louer 2012, 136). In April 1998, for example, Sadiq revived congregational Friday prayers, which had been suspended by Iraq’s previous grand ayatollahs until the return of the Mahdi (Filiu 2011, 146). These Friday gatherings very quickly developed a political, anti-Saddam character, illustrating the difference between Sadiq’s political messianism and the more quietist and apolitical beliefs of his rivals.

The current Sadrist leader, Muqtada al-Sadr, cannot claim the status of marja or even mujtahid (authority in Islamic law). Ironically, however, neither the lack of credentials nor hostility from the Shia clerical establishment have dented Muqtada’s popularity amongst his followers, who are mostly underprivileged youth from deprived areas in Baghdad (Louer, 2012, 137). In fact, young Sadrists seem to identify very strongly with Muqtada’s outsider status in the clerical and political scene and regard him as a quasi-messianic figure.

Sadrist Adaptations and Innovations

After the US-led military intervention and the fall of Saddam in 2003, Muqtada injected political urgency into previously suppressed Shia rituals and practices. On 11 April that year, for example, he gave his first sermon in his martyred father’s mosque in Kufa, calling on his followers to walk to Karbala on foot (Cockburn 2008, 16). This was to commemorate the martyrdom of Imam Husayn (the grandson of the Prophet Muhammad and son of the Prophet’s cousin and son-in-law, Ali) and draw inspiration from it. In this way, the Sadrists were able to tap into the revolutionary significance of specific Shia events and rituals such as Ashura (which commemorates Husayn’s death) and Arbain (another commemoration of his death, marked forty days after Ashura).

As large as these processions were, they went largely unnoticed in the Western media at the time (Cockburn, 2008, 17). Yet, as rituals that are central to Shia identity and group solidarity, Ashura and Arbain became increasingly salient as Sunni militants began attacking Shia targets.

A short video explaining the significance of Ashura in post-Saddam Iraq, produced by Al Jazeera, can be viewed below

Revolutionary or politicised interpretations of Shia rituals were not commonplace, however, before the 1979 Iranian revolution. Members of the al-Sadr family played an important role in catalysing such interpretations outside of Iran. In the 1960s, for example, Musa al-Sadr had already transformed the commemoration of Karbala in 1960s Lebanon from a ritual of fatalism to a ritual of rebellion (Louer 2012, 12). Starting from the 1990s, the sermons during congregational Friday prayers—revived by Sadiq al-Sadr—became important channels for Sadrist sentiments to be circulated even before the fall of Saddam and the US occupation in 2003 (Cockburn 2008, 105).

Muqtada, the current Sadrist leader, has also effectively utilised particular symbols to consolidate and grow the Sadrist Movement. He changed the name of his powerbase in Baghdad from al-Thawra or Saddam City to Sadr City (Cockburn 2008, 128). Also, when Muqtada was trapped in Kufa in April 2004, he denounced President George W. Bush as a modern-day Yazid, the second Umayyad caliph under whose reign Imam Husayn was killed in Karbala (Cockburn 2008, 22).

Additionally, the Sadrist militia wing was given a messianic name—the Mahdi Army, which rapidly established its reputation as a Shia self-defence force. In Shia eschatology, the army of the Mahdi is also known as the ‘army of wrath’ which treats its opponents with unforgiving brutality (Filiu 2011, 147). The Sadrists’ explicit reference to apocalyptic heritage was meant to strike fear not only amongst their foreign or Sunni foes but also their Shia rivals. The Army emerged swiftly after Al Qaeda in Iraq, the Sunni militant group, bombed Ashura commemorations in 2004, killing 270 and wounding 570 (Cockburn 2008, 144).

The Sadrists are not categorically anti-Sunni, however. Muqtada has been willing to cooperate with anti-occupation Sunni leaders as long as they condemn deadly attacks on Shia civilians—which many have been reluctant to do (Cockburn 2008, 166). His pronouncements, however, are not always explicitly apocalyptic or messianic. Rather, Muqtada often makes general statements that provoke messianic or millenarian speculation amongst his followers, which he does little to dispel. At the same time, he draws more heavily upon the theme of martyrdom—based on the history of the political assassinations of his family members—to punctuate his messages (Filiu 2011, 148–149). This rhetorical strategy is partly what endows his position with populist appeal.

Controversies

The US-led military invasion of 2003 catalysed significant episodes of instability within Iraq, interspersed with fragile transitions to democratic government. Sectarian violence between Sunnis and Shias also became complicated by intra-Sunni and intra-Shia rivalries, which developed alongside cross-sectarian anti-US attitudes. Within this larger context, the Sadrists have, at different points, been both victims and perpetrators of violence and other controversies.

The regime of Saddam Hussein carried out killings of prominent leaders of the al-Sadr family—Baqir in 1980 and Sadiq (and his two older sons) in 1999. After Saddam was overthrown in 2003, however, intra-Shia violence was triggered when Muqtada’s supporters killed Abd al-Majid al-Khoei, who was returning from exile in London where he headed the Khoei Foundation, a charitable organisation (Louer 2012, 91). Abd al-Majid’s father-in-law, Abu al-Qasim al-Khoei, was previously the Grand Ayatollah and marja (model for emulation). The killing of Abd al-Majid happened amid Muqtada’s increasing animosity towards those whom he accused of collaborating with Saddam’s regime, especially clerics he referred to as the ‘silent marjaiyya’. These included Ali al-Sistani, who had succeeded Abu al-Qasim al-Khoei as Grand Ayatollah. In the days after the murder of Abd al-Majid, the Sadrists surrounded the house of al-Sistani, demanding that he leave Iraq and go back to Iran.

This violent clerical rivalry is also characteristic of the milieu of Shia militias in post-Saddam Iraq, which include the Sadrist Movement’s Mahdi Army (disbanded in 2008 but now revived as the Peace Companies). Other prominent militias include the Iran-backed Badr Organisation, whose parent organisation is the Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution in Iraq (SCIRI), now renamed the Supreme Islamic Iraqi Council (SIIC) (Louer 2012, 87). There are also the militias that splintered from the Mahdi Army—Asayyib Ahl al-Haq (League of the Righteous) and Kataib Hizbullah (Hizbullah Brigades) (Amnesty International 2014, 17). These Shia militias emerged alongside militant Sunni jihadi groups that were opposed to the US-led occupation, the most prominent being the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS).

For more background on Iraq’s Shia militias, see the short video produced by The Guardian below

For a more recent and in-depth look, see the video produced by Al Jazeera below

ISIS—now known simply as the Islamic State (IS)—is itself responsible for massive human rights abuses within territories under its control. Its fighters also frequently carry out bomb attacks that target Shia civilians in Baghdad and elsewhere. The Shia militias have retaliated by abducting and killing Sunni men with impunity. According to Amnesty International (2014, 4), victims have been abducted from homes, workplaces or sectarian checkpoints on the road set up by the militias. Many were later found dead, usually handcuffed and shot in the back of the head. Some victims were killed even after their families paid large ransoms.

Although the principal perpetrators of anti-Sunni violence are the Shia militias, Amnesty International ultimately holds the Iraqi government responsible for its incapacity or unwillingness to protect civilian populations. There is even evidence that the government has funded or indirectly supported these militias (Amnesty International 2014, 5).

The scenario is complicated by the existence of anti-ISIS Shia militias, active in Iraq and backed by the Iranian government, which initially operated in neighbouring Syria (Al-Tamimi 2015, 80–81). When ISIS began gaining control of territories in Iraq, many of these militias turned their attention to Iraq as well. There are thus Shia militia groups that see Iraq-Syria as a single battlefield in their fight against ISIS and those, like the Sadrist Movement’s Peace Companies, that focus on Iraq and can be critical of Iranian influence (Al-Tamimi 2015, 81–82).

The Sadrists—through the Mahdi Army and its splinter groups—have thus been part of this continuing climate of violence and war crimes. The Mahdi Army was especially influential during the sectarian violence that erupted from 2006 to 2008. At that point, the Bush administration even denounced Muqtada al-Sadr and the Sadrists as the greatest terrorist threat to the stability of Iraq (Al Jazeera and news agencies 2008).

The Sadrists are also known for their strict imposition of conservative religious rulings in the areas under their control, for example regarding gender segregation and women’s dressing (Cockburn 2008, 173). Yet they are also pragmatic on certain issues. For example, in 2016, Muqtada called for an end to violence against people who did not conform to gender norms, including those perceived to be lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender (LGBT) (Human Rights Watch 2016). This was in response to the waves of extra-judicial killings of ‘effeminate’ men and youths in the ‘emo’ subculture—perceived in Iraq as followers of heavy metal or rap music—by members of the Mahdi Army.

Muqtada soon reactivated the Mahdi Army, however, when sectarian violence erupted in 2006 and the Sadrists gradually withdrew from government (Godwin 2012, 453). After the surge of coalition troops to fight the 2007 Sunni insurrection that also threatened to crush the Mahdi Army, Muqtada declared a ceasefire and moved to Iran in self-imposed exile. The Sadrists then returned to participate in the elections of 2009 and 2010 and performed relatively well in both (Plebani 2014, 6).

Muqtada became increasingly critical of the government of the then Prime Minister Nouri Al-Maliki of the Dawa Party, which he initially supported. In 2013, Al Ahrar—the Sadrist Movement’s political wing—joined a coalition of anti-Maliki Shia parties which included SIIC, their one-time rivals (Plebani 2014, 7–8).

Yet, in 2014, Muqtada announced his formal withdrawal from politics. This announcement, however, appears to be tactical—Muqtada still retains control of the vast network of charities, schools and institutions associated with the Sadrists. He remains the spiritual leader of the Sadrists while Dia al-Asadi is the political leader of Al Ahrar. In the 2014 elections, Al Ahrar won 28 out of 328 available seats in the Iraqi parliament. In 2016, Muqtada and other Sadrist leaders led popular protests in Baghdad, calling on Prime Minister Haider Al-Abadi to eliminate corruption and change the ‘whole system’ of government (Arraf 2016, Chulov 2016).

For a deeper look at the 2016 Sadrist uprisings in Baghdad, see Al Jazeera’s coverage below

Muqtada’s influence on the Sadrist Movement, however, has never been entirely stable. He has not been able to control splinters from emerging, even from the Mahdi Army, nor has he been able to rein in the wanton violence perpetrated by some of his supporters. This might partially explain his reluctance to participate in politics more fully.

More generally, the Sadrist Movement’s fluctuations between violence and peaceful political activity are a good example of the development of political millenarianism among Shia populations in the Middle East. By implicitly drawing upon millenarian and messianic rhetoric and symbols, Muqtada has turned his marginal position as a religious leader into an advantage (Louer 2012, 137). When rival clerics denounced his lack of religious credentials, his followers celebrated his ‘outsider’ status as part of their grievance and protests against a corrupt regime. This is why the major Shia political players have not been able to exclude the Sadrists entirely, especially when forming electoral pacts.

At the same time, Muqtada’s pragmatism continues to result in surprising developments. Most recently, in August 2017, he visited the royalty and Sunni leaders in the United Arab Emirates. This came after he visited Saudi Arabia—traditionally hostile to Iran and to Shiism—and referred to it as a ‘father figure’ in the region (Cafiero 2017). Muqtada’s visit to these Sunni-led Gulf monarchies is also significant in light of the Iraqi government’s advances against the Islamic State earlier in 2017. The majority of Iraqi Shias see the Saudis as responsible for the rise of ISIS and it is unclear how Muqtada will try to reconcile their anti-Saudi sentiments with his recent visits to the monarchy. It is possible, however, that Muqtada’s recent overtures are part of a longer-term strategy to diversify his pool of support within and outside Iraq and to dilute the influence of his opponents (Alaaldin 2017).

Further Information

Academic References

Adamec, Ludwig W. 2009. “Shiism” in The A to Z of Islam, Second Edition, 286–88. Plymouth: Scarecrow Press.

Al-Tamimi, Aymenn Jawad. 2015. “Shii Militias in Iraq and Syria.” Middle East Review of International Affairs 19 (1): 79–83.

Beattie, Hugh. 2013. “The Mahdi and the End-Times in Islam” in: Sarah Harvey and Suzanne Newcombe (Eds.), Prophecy in the New Millennium: When Prophecies Persist, Ashgate Inform Series on Minority Religions and Spiritual Movements. 89-103. Ashgate, Farnham.

Cole, Juan. 2002. Sacred Space and Holy War: The Politics, Culture and History of Shiite Islam. New York: I.B. Tauris.

Esposito, John L. ed. 2004.“Shii Islam.” In The Islamic World: Past and Present, Volume Three: 81–87. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Filiu, Jean-Pierre. 2011. Apocalypse in Islam. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Godwin, Matthew J. 2012. “Political Inclusion in Unstable Contexts: Muqtada Al-Sadr and Iraq’s Sadrist Movement.” Contemporary Arab Affairs 5 (3): 448–56.

Louer, Laurence. 2012. Shiism and Politics in the Middle East. London: Hurst & Company.

Plebani, Andrea. 2014. “Muqtada Al-Sadr and His February 2014 Declarations. Political Disengagement or Simple Repositioning?” Analysis 244: 1–11.

Reports by human rights organisations:

Amnesty International. 2014. “Absolute Impunity: Militia Rule in Iraq.” London: Amnesty International. Available at: https://www.amnesty.org/en/doc....

Human Rights Watch. 2016. “Iraq: Cleric’s Call Against Anti-LGBT Violence.” Human Rights Watch. August 18. Available at: https://www.hrw.org/news/2016/08/18/iraq-clerics-call-against-anti-lgbt-violence.

Popular References

Cockburn, Patrick. 2008. Muqtada Al-Sadr and the Battle for the Future of Iraq. New York: Scribner.

Online news and other resources

Al Jazeera and news agencies. 2008. “Profile: The Mahdi Army.” Al Jazeera. April 20. Available at: http://www.aljazeera.com/news/....

Alaaldin, Ranj. 2017. “Could Muqtada Al-Sadr Be the Best Hope for Iraq and the Region?” Brookings. August 21. Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/blog....

BBC. 1990. “1990: Iraq Invades Kuwait.” BBC, August 2. Available at: http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisda....

Arraf, Jane. 2016. “Iraq: Muqtada Al-Sadr’s Green Zone Demonstration - AJE News.” Al Jazeera. March 29. Available at: http://www.aljazeera.com/news/....

Cafiero, Giorgio. 2017. “What’s next for GCC-Iraq Ties after Sadr’s UAE Visit?” Al-Monitor. August 15. Available at: http://www.al-monitor.com/puls....

Chulov, Martin. 2016. “Protesters in Iraq’s Green Zone Begin to Withdraw.” The Guardian. May 1. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/wo....

Momen, Moojan. 1985. “An Introduction to Shii Islam (Excerpts).” Baha’i Library Online. Available at: https://bahai-library.com/mome....

© Shanon Shah 2021

Note

This profile has been provided by Inform, an independent charity providing information on minority and alternative religious and/or spiritual movements. Inform aims to deliver accurate, balanced, and reliable data. It relies on social scientific research methods, primarily the sociology of religion. Inform welcomes feedback, comments, corrections, or further information at inform@kcl.ac.uk.